What’s the Most Beautiful Building in the World?

The West has forgotten what beauty means.

We either reduce it to surface-level Instagram aesthetics or we worship the oppressive grandeur of past empires. But beauty, properly understood, is neither. It’s a union of form and purpose—a moral ideal built in stone.

You know those posts on X that ask or state, “What’s the most beautiful building in the world?” The replies are always the same: a cathedral in Florence, St. Peter’s Basilica, some baroque palace in France, the Taj Mahal in India. Then come the contrarians who post Soviet apartment blocks and say this is beauty, mocking the very notion.

Both sides get it wrong.

Yes, these buildings contain astonishing craftsmanship. But ask yourself: what are they for? What is their essence?

As historian Georges Duby has put it:

Abbot Suger’s Gothic project at Saint‑Denis was deliberately conceived as a ‘monument of applied theology,’ a visible expression of the Church’s moral and institutional authority.

Whether Gothic, Renaissance, or Baroque, these buildings share the same essence—they were constructed to humble man, not glorify him.

Beauty, in these cases, becomes a tool of subjugation—a velvet chain.

These cathedrals were monuments to mysticism, built to glorify institutions that demanded obedience, sacrifice, and self-abnegation. The beauty is real, but so is the context. Beauty divorced from moral purpose is not innocent. It can be used to elevate truth—or to sanctify servitude.

Take the Cologne Cathedral. I’ve seen it often. It’s not beautiful. It’s monstrous. A black spire rising like a threat. Gargoyles leering from every edge. There is no light, no human warmth—only submission. What does it represent? A moral ideal that says: you are nothing. That your role in life is to kneel, to suffer, to cower before something higher. It is not an expression of man’s greatness but of his supposed unworthiness.

And worse: it is nothing more than an aggrandised cemetery—a memorial to all those who needlessly wasted their lives building this awful monument, a monument raised to serve the arrogance of the pathetic rulers of the time. The structure, drenched in the sacrifices of others, feigns glory. Workers fell from scaffolding, were crushed by stones, and died from lung disease—this building is literally constructed on human bones, not just metaphorically built through human sacrifice.

This is what I mean when I say these buildings are built against man—literally and figuratively.

These buildings are not built for man—they are built against him. Their size exists for belittlement. They are not grand in celebration but in domination. They are not closer to God in spirit but in intent: to remove man from the centre of the universe.

Contrast that with a place like the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. I’m not saying it’s my favourite building in the world, but it makes the point. It’s monumental, yes. Imposing, yes. But it doesn’t crush you. It doesn’t exist just to be large. Its scale serves a purpose: to house some of the greatest works of art in human history. It welcomes you in. It asks you to rise to meet what it contains.

That’s the essential difference. I’m not against size or splendour—I’m against empty monumentality, the kind that exists only to aggrandise its builders or belittle the viewer. There is a world of difference between a building that is large in order to serve something great and one that is large to make you feel small. One elevates man. The other erases him.

And here’s the real point:

Beauty is the union of purpose and aesthetics. It is the marriage of the moral and the sensory.

You can have something that is pretty, ornate, and pleasing, but that doesn’t make it beautiful. The word beautiful should be reserved. It should be sacred. For something to truly earn that title, it must embody a positive moral purpose through a form that uplifts the soul.

The ancient Greeks understood this. They didn’t see beauty as decoration or divine intimidation. For them, kalos kagathos—“the beautiful and the good”—was an ideal of harmony between moral virtue and physical form. As Aristotle put it, “Virtue aims at the beautiful.” A beautiful life wasn’t just lived well—it was lived nobly, with visible purpose.

We have lost that unity. Today, beauty is either reduced to aesthetic surface or inflated into spiritual vagueness, severed from action, function, and life.

This is the deeper issue: what we call “beauty” today is often a symptom of a false metaphysics. Either beauty is treated as pure surface, something material, divorced from meaning. Or it’s treated as something “spiritual,” cut off from function and reality. But real beauty is neither of these. True beauty is the marriage of body and soul, of spirit and structure. It is the visible expression of a meaningful purpose.

The buildings that actually embody life: New York skyscrapers, the Sydney Opera House, museums, train stations, and cafés that serve humanity—those are our modern cathedrals. They are built for joy, for ambition, for us. And that matters. Because beauty is not just decoration. Beauty is a moral ideal. It is the form of a value.

And that’s why I’m writing this.

Because I want beauty to mean more.

Not as an aesthetic indulgence, we outsource once a year while travelling Europe, snapping photos of pretty ruins and calling it culture.

Beauty must not be rare. It must not be foreign. It must not be passive.

Beauty must be ever-present in our everyday lives—woven into our streets, our homes, our clothes, and our public spaces.

Not because it is a “duty,” but because it is a virtue. A necessity.

For human flourishing. For human pride. For life on Earth.

Let’s stop mistaking intimidation for beauty. Let’s stop worshipping aesthetics ripped from their context.

A truly beautiful building is one that says: You belong here.

You are worthy of greatness.

Enjoyed this piece?

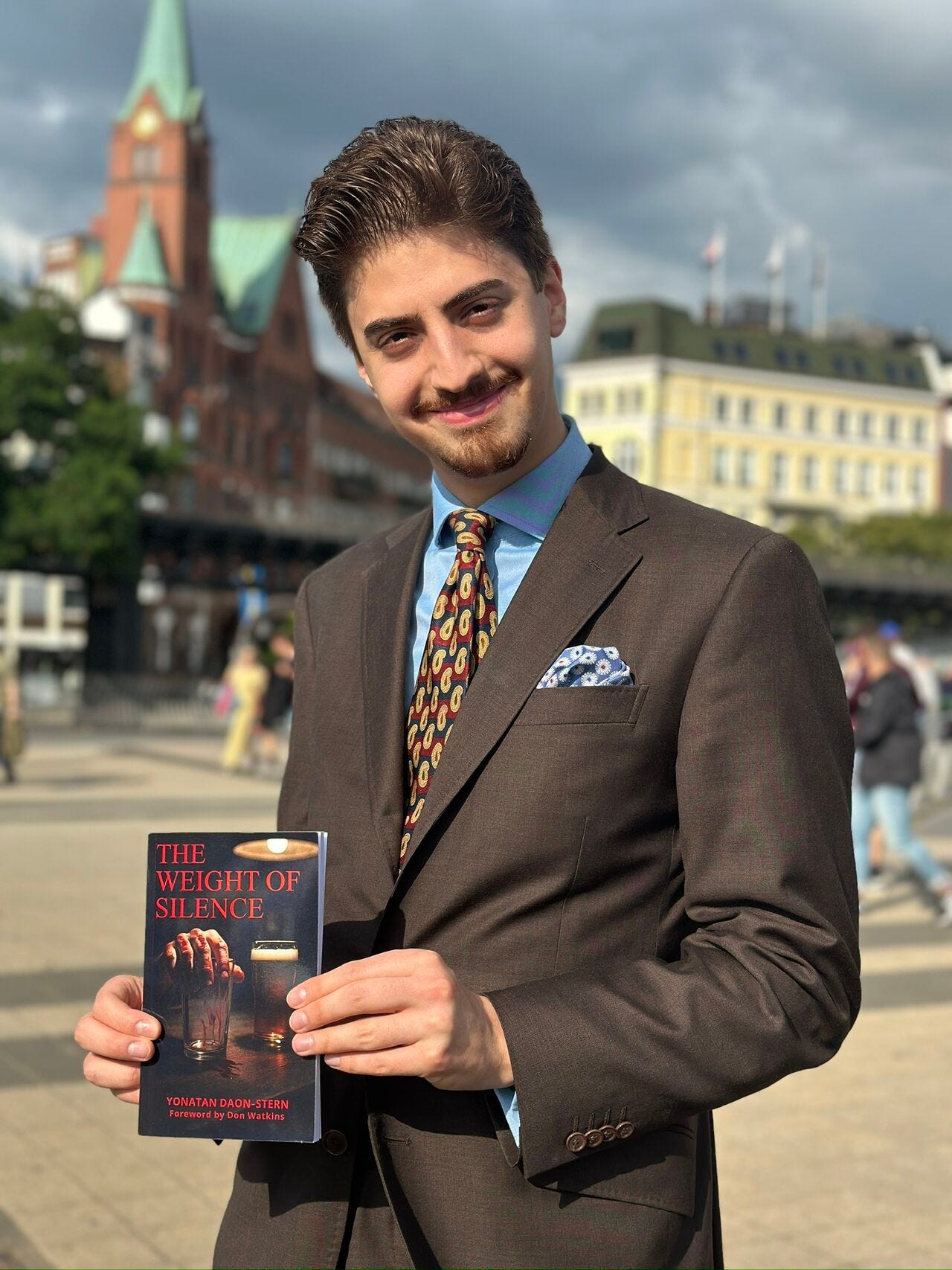

I’ve just released my debut novella, The Weight of Silence. You can buy it on Amazon.

If you want to support my broader work—fiction, essays, and everything in between—consider becoming a monthly member or making a one-time contribution here. Every bit helps me create more and better.

Fascinating ideas, and thank you for sticking your neck out and expressing them. Medieval religious architecture (Islamic as well as Christian) does have an oppressive quality to it, even if it's also ornate in ways that would have stood out as appealing in the relatively dull general environment of medieval cities. And there's no denying that the great cathedrals and palaces were built partly as assertions of power by the mighty over ordinary individuals.

If American monumental architectures is much more obviously ugly, well, it's the same kind of assertion of power by the mighty, except it's corporate power rather than religious, while most of the aesthetic sense of ornateness from the Middle Ages has been lost.

"they were constructed to humble man, not glorify him" Yes, exactly. But your overall critique, to me, is ahistorical. Your assumption that a piece of architecture *should* glorify man would strike any medieval cathedral builder or European citizen of the time as blasphemy. They wouldn't even understand it. Because you've omitted God from the equation. It was not about 'humbling' man in the sense of subjugation, it was about glorifying God through architectural design, the spires, the ceilings and floor plans, the light through stained glass etc. to show man his 'humble' place in the order of things but at the same time lift his spirit closer to the Divine. Properly understood, cathedrals as places of worship were a person could find liberation from his fallen humanness, his sin, not enslavement. This was exactly the moral purpose that a cathedral was intended to express and serve. You might not agree with that, but I think you need to acknowledge the truth of it in an historical context.

Of course, that doesn't make every cathedral automatically beautiful, some were obviously more successful in achieving their vision than others.

I do agree with your mission, here, though, to recover a sense of beauty in the world as it's true that the modern age has for more than a century now essentially turned against the whole idea. And the connection with moral purpose is definitely important. To glorify man? Maybe, but personally, I think that effort has brought us to some pretty dark places.