Tel Aviv: The Last Western Dream

I meant to publish this tomorrow, on Tel Aviv’s official birthday. But today is mine—and I can’t think of a better way to celebrate than by releasing the piece that means the most to me.

A tribute to the city I was born in.

The city from whose fabric I am cut.

The place where I was molded.

The greatest place on earth.

On April 11th, 116 years ago, something extraordinary happened.

A city was founded—and its name was Tel Aviv.

When we imagine the founding of something great, we picture grand oil paintings: the signing of the U.S. Declaration of Independence, Napoleon’s coronation, or the German Empire proclaimed in the Hall of Mirrors.

But the founding of Tel Aviv?

It had none of that grandeur. No palace. No anthem. No ceremony.

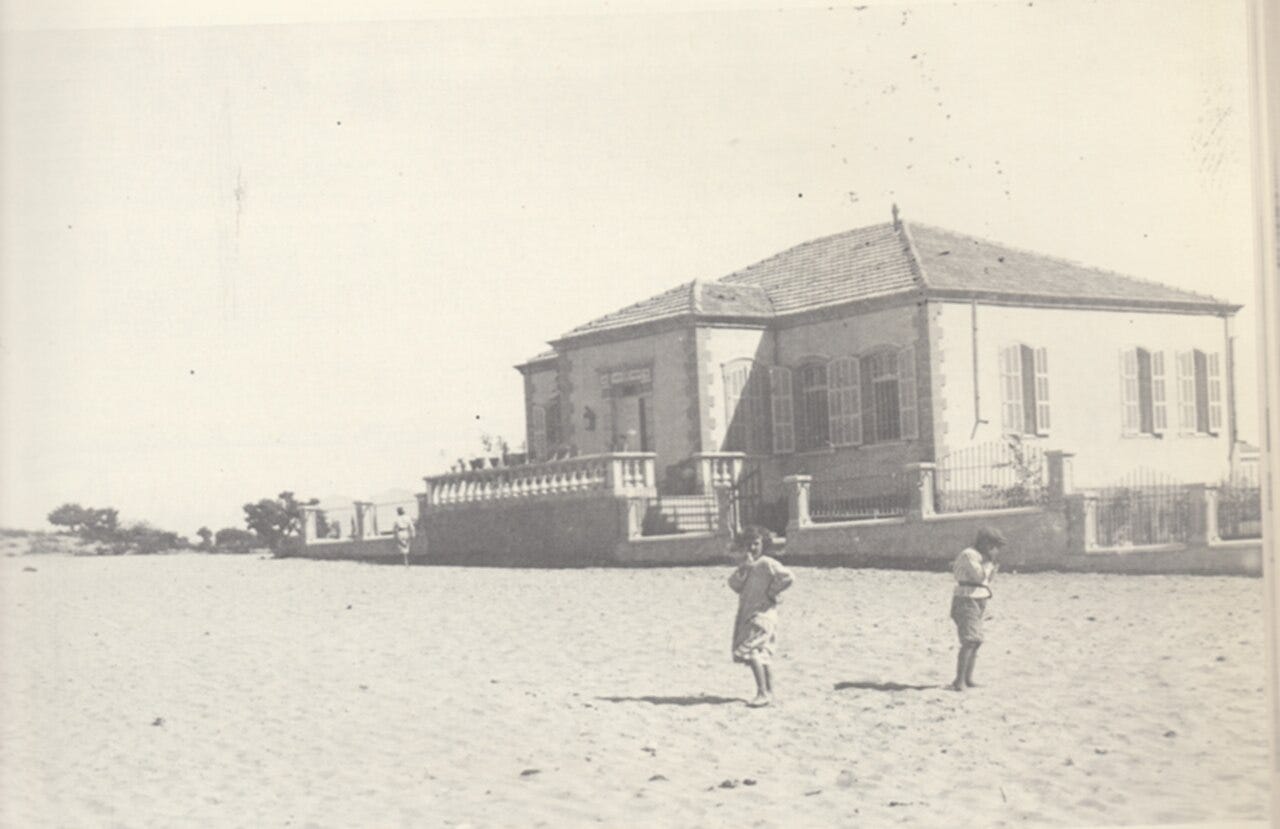

What we have is an image—one of striking simplicity.

The Seashell Lottery

Sixty-six families stood together on an empty stretch of sand dunes, only a few kilometres from the ancient port city of Jaffa. They wore European clothes under the Middle Eastern sun—some shaded by straw hats, others by felt fedoras—and held seashells in their hands. Written on these seashells were names and numbers. One by one, shells were drawn, matching each family not to a house, but to bare sand—to a plot of pure potential, in a place that did not yet exist: a city.

There were no buildings, no roads, no running water. Just wind, sand, and the audacity to imagine something lasting. Not another shtetl. Not a ghetto. Something new.

They founded Tel Aviv without fanfare, without marble columns.

They founded it with seashells, from nothing.

The Man Who Stood Above the Dunes

Akiva Aryeh Weiss (1868-1947), the visionary behind this gathering, was the man who stood above. Weiss, a goldsmith by trade and a Zionist dreamer by conviction, had arrived from Europe with the radical idea that Jews should not simply settle but build a modern, vibrant, and proudly Hebrew-speaking city.

In his vision, it wasn’t only the language that had to be Hebrew—but the work, too. This idea—Avodah Ivrit, Hebrew labour—was central to the Zionist awakening. For centuries, Jews in exile were confined to ghettos, forbidden from owning land, barred from trades, or forced into marginal professions.

Avodah Ivrit was not about exclusion or ethnic hostility—it was about independence. A people who had long been denied the right to work freely would now build with their own hands—not to demean others, but to redeem themselves. Here, for the first time in modern history, Jews would lay their own roads, raise their own walls, and plant their own trees. It wasn’t just work—it was redemption through creation.

Even the language was a revolution. Hebrew had not been spoken as a mother tongue for nearly two thousand years. Most of the city’s founders had grown up speaking Russian, Yiddish, German, or French. Choosing Hebrew was not natural—it was deliberate. It was the glue of a new national identity, the common thread uniting immigrants from dozens of backgrounds into one people with one purpose.

Weiss watched his audacious dream begin to unfold: the building of the first Hebrew city—not just in language, but in outlook, in energy, and in soul. The first city where Jews would live not as strangers or survivors, but as creators.

The words Altneuland stirred me with tremendous power—both openly and in secret. It was as if they demanded action from me at every step. I felt as though I had received a command from above: Say little, do much.

— Akiva Aryeh Weiss, journal

This was no vague utopia. Weiss had a concrete vision—documented in the official founding prospectus of Ahuzat Bayit, penned in 1906 on the symbolic day of Tisha B’Av, the Ninth of Av—the traditional day of mourning for the destruction of the Jewish Temples and the beginning of exile. Choosing this date was no coincidence. It was a conscious statement: here, on the same day Jews had long commemorated their loss, they would now declare their rebirth.

We must promptly acquire a proper plot of land on which to build our homes. Its location should be near Jaffa, and it shall become the first Hebrew city, where 100 percent of the residents are Hebrews; where Hebrew is spoken, where cleanliness and purity are upheld, and where we shall not follow the ways of the Gentiles.

In this city, we shall arrange streets with roads and sidewalks, install electric lighting, and bring fresh water into every home through pipes from the springs of salvation…

Just as the city of New York marks the main gateway into America, so too must we develop our city—until it becomes, in time, the New York of the Land of Israel.

— Akiva Aryeh Weiss, Prospectus of the Temporary Committee for the Establishment of Ahuzat Bayit, Jaffa, Tisha B’Av, 1906

A City Engineered to Scale

This early vision of piped water wasn’t just aspirational—it became foundational. By planning for modern infrastructure from the outset, Tel Aviv positioned itself to grow, absorb new neighbourhoods, and connect its parts like a real city.

Weiss envisioned Tel Aviv as a “garden city,” blending modern urban planning with greenery, cleanliness, and order—an intentional alternative to the chaos of Jaffa and the crammed shtetls of exile. Streets would be wide, homes would have gardens, and the city would feel both civilised and free. This vision directly gave birth to Tel Aviv’s iconic boulevards and its famously walkable character—an urban experience designed for human flourishing, not just for function. It was precisely this kind of foresight that allowed the dream to scale.

From Nothing to Statehood

Meir Dizengoff (1861–1936) stood among the families on that April morning, a man whose name would soon become synonymous with Tel Aviv itself. Born in Bessarabia and shaped by the Zionist fervour of Odessa, Dizengoff helped establish the Ahuzat Bayit society in 1906.

At the seashell lottery, he secured his own plot of sand, becoming one of the city's first residents. He was soon elected head of the township committee and later served as Tel Aviv’s first mayor from 1921 until his death. Under his leadership, the city transformed from empty dunes into bustling boulevards, cafés, and elegant Bauhaus buildings.

Over the years, Dizengoff expanded his modest home, eventually turning it into the Tel Aviv Museum of Art. He willed the house and its collections to the “children and residents of Tel Aviv.”

It was here that, on May 14, 1948—long after Dizengoff himself had passed—the State of Israel was officially proclaimed. Thus, Dizengoff’s home, originally just a seashell-assigned plot on bare sand, became the symbolic birthplace of an entire nation.

The Name, the Spirit, and the Streets

But Dizengoff wasn’t the only builder of the city’s soul. Others stood there too—educators, idealists, men of vision and steel. Among them was Menahem Sheinkin (1871–1924), who also stood among the crowd, a thoughtful and pragmatic Zionist whose ideas would profoundly shape Tel Aviv's character. Born in Belarus and educated in Odessa, Sheinkin was an advocate of progress, industry, and urban life. He rejected the socialist Zionist ideal that exalted agriculture above all, arguing passionately that craftsmen, artisans, and entrepreneurs were equally pioneering in building the Jewish homeland.

In his words:

And perhaps the ordinary Jewish craftsman, the family man, is he not also truly a pioneer? Has he shown less courage and national devotion by coming to Palestine than the young agricultural pioneers who claim seniority?... Has he not demonstrated enough dedication to be worthy of the name 'pioneer'?

Sheinkin pushed tirelessly for Tel Aviv to be an industrious city—a place of workshops, trades, and bustling commerce. He helped establish neighbourhoods, markets, and infrastructure to support economic growth, believing that true independence came from industry and self-sustaining labour.

It was Sheinkin who first suggested the symbolic name Tel Aviv, drawn from the Hebrew translation of Theodor Herzl’s (1860-1904) utopian novel Altneuland—a name that would embody the dream of Jewish renewal and modernity in the land of Israel. Herzl, the founder of the Zionist movement, had envisioned a Jewish society reborn through progress, science, and culture. Sheinkin and his peers were now turning that vision into sand and stone. Today, a vibrant street bearing Sheinkin’s name—lined with boutiques and espresso bars—commemorates the industrious, practical spirit he championed.

They Built a School Before a Road

Alongside Sheinkin and Dizengoff, Dr. Yehuda Leib Metman-Cohen (1869–1939) stood on the sand, envisioning something extraordinary—not merely a school, but a cultural landmark. With his wife, Fania, he had founded the Herzliya Hebrew Gymnasium in 1905, the world's first Hebrew-language high school. At the 1909 land lottery, Metman-Cohen secured a prominent plot on Herzl Street, knowing exactly what he would build there.

Shortly after, the cornerstone for the new building was laid—again on Tisha B’Av, the day of national mourning for the destruction of the Temples. Like Weiss’s founding manifesto, this was a deliberate act of historical and spiritual defiance. Once more, Tel Aviv’s founders used the day of destruction to symbolise revival—a living testament to how rooted they were in Jewish history and how determined they were to resurrect Jewish life, not in sorrow, but in strength.

The decision to make education the city’s first public institution was no coincidence. It reveals the character of Tel Aviv’s founders. In a place without paved roads, they built a school. And not just any school—the Herzliya Gymnasium, constructed in the image of the ancient Jewish Temple. Its style evoked holiness, a deeply rooted connection to the Land of Israel—but its content was modern, secular, and fiercely rational. No mysticism, no dogma. Just education, in Hebrew, for a generation that would build the future. It was a powerful symbol: this city would rise not just from sand, but from ideas.

The building itself was an architectural marvel. Designed to resemble the ancient Jewish Temple, it featured a commanding central tower, stately symmetry, and a façade that radiated purpose and pride. It became Tel Aviv’s first public building and the cultural heartbeat of the new city, hosting lectures, concerts, community events, and shaping generations of Hebrew-speaking youth.

But in 1962, in an act still mourned today, the Gymnasium was demolished to make way for the Shalom Meir Tower. What rose in its place was taller—but not greater. The loss of the Gymnasium remains one of Tel Aviv’s most painful cultural wounds: the destruction not just of a building, but of a symbol.

A Western Dream, Made Real

I keep returning to that image—the sand, the seashells, the quiet, improbable beginning of something extraordinary. That photo says more than a thousand words ever could. I think of where these men and women came from—particularly those from Europe's great cities: Vienna, Paris, and Odessa. They left behind paved streets, electric lights, theaters, and cafés.

Unlike those who arrived in later decades—escaping genocide, arriving with nothing but trauma—these pioneers came deliberately, with their suitcases, their carefully chosen clothes, and their pride.

They weren’t fleeing destruction—they were choosing creation. Not refugees, but visionaries. They chose to build, to change the world according to their ideals, to construct a city of flourishing Hebrew life. No more ghettos, no more hiding—just pride, vision, and sand.

At first glance, it seems like a retreat—to malaria-infested swamps, poverty, and uncertainty. Yet only five short years after that image was captured, Europe itself plunged into chaos: trench warfare, gas attacks, and destruction. As Europe descended, Tel Aviv rose—slowly, deliberately—with boulevards, beaches, and cafés. They dreamt of cappuccinos and croissants in a land of nargilas and bitter coffee. And then they made them real.

Tel Aviv was built on the last fumes of the Enlightenment, when the dream of progress had all but died in the European trenches. But here, on sand and in Hebrew, it took one final breath—and came to life.

In an ironic twist of history, these pioneers weren't running away from progress, but carrying it forward. They continued the Western dream of the Industrial Revolution, Enlightenment ideals, and civilised beauty precisely at the moment Europe lost its grip.

Indeed, what great European city was founded after 1909? What new nation was built upon hope rather than destruction? If anything, Europe's twentieth century saw mass murder and ruin, while Tel Aviv—this improbable city born from nothing—saw renewal, growth, and progress. Tel Aviv is not just a city—it was the last great city founded by the West.

In that photograph, in that act of founding, they weren't abandoning Western civilisation. They were saving it.

Tel Aviv Today: The Dream Lives On

Today, Tel Aviv is a city of art, vibrant cafés, world-class restaurants, golden beaches, and gleaming skyscrapers. And, of course, home to some of the most beautiful, daring, and self-assured people on earth. Proud, Hebrew-speaking Jews who build companies, launch ideas, speak their minds, and defend their freedom fiercely. Israel’s start-up capital was itself a start-up from day one—founded by visionary entrepreneurs armed with nothing but seashells and a dream. The entrepreneurial spirit, the unapologetic confidence, the refusal to ask permission—that didn’t vanish with the dunes. It lives on in every corner café and every glass tower.

All of this exists thanks to those incredible sixty-six families who stood on a dune, holding seashells, daring to imagine something new.

Tel Aviv’s founding is not just history. It’s proof. Proof that something lasting and magnificent can be built from nothing but a rational vision and the courage to pursue it relentlessly. The dunes may be gone, but their lesson remains: human beings, driven by purpose and pride, can change the world to match their ideals. This city is a living monument to that truth.

In a cynical world that doubts whether greatness can still be achieved, Tel Aviv stands as a reminder: it is possible.

And Then They Will Speak of It

This is only the beginning of what must be said about Tel Aviv’s founders. I wish I could tell every story here—the artists, the teachers, the builders, the dreamers—but that deserves a book of its own. Maybe one day.

As the city he built blossomed from an idea into a civilization, Weiss himself knew that his contribution would one day be recognised, even if not in his lifetime. In a 1910 letter to a friend from abroad, he wrote:

6 Tammuz, 5670 (July 1910)

Yosef, my friend,

We’ve already moved into our new home in the new neighborhood of Tel Aviv, among the members of Ahuzat Bayit, and we are very pleased with the new surroundings…

I was privileged to begin and complete the construction of a new and beautiful city in the Land of Israel, and I greatly advanced the development of the settlement—for the better.

In Russia, there was no Ahuzat Bayit, no Tel Aviv, no Hebrew Gymnasium, and many other things we now have.

I passed on a proud gaze to our brothers who are not yet enlightened, who still do not see the value of this endeavor.

But they will come, and they will speak of it, and of me, in very warm words.

And then all the slanderers will dry up and disappear—all those who tried to ruin the construction.

That time is not far off, and with the greatest patience, I await it

Akiva Aryeh Weiss

He wrote these words when Tel Aviv was little more than sand, a few homes, and an unfinished school. And yet, he called it “a new and beautiful city.” Why? Because it wasn’t about what already stood—it was about what it meant. In the Hebrew Gymnasium, he saw more than just a building; he saw a future. In those modest homes, he saw independence. Compared to this, the grandeur of Europe meant nothing.

And indeed, as he said, here I am, 116 years after your heroic vision and relentless labour—I speak of you in very warm words.

A very happy 116th birthday, my dear Tel Aviv!

More will be said of Weiss, Herzl, Dizengoff, and the many heroic visionaries whose work and ideals gave birth to the last great city of the enlightenment.

Thank you for reading Philosophy: I Need It. If you enjoyed it and want to see more content, consider supporting me by clicking the button below. Every dollar counts.

It’s quite disappointing that the original gymnasium was torn down, however, on the positive side, the Shalom Meir Tower was the first skyscraper in the Middle East. That also represents progress and civilization in some way.

Mazal Tov! It’s a really inspiring essay. “Tel Aviv’s founding is not just history. It’s proof. Proof that something lasting and magnificent can be built from nothing but a rational vision and the courage to pursue it relentlessly.” - in what sense do you think the early Zionist vision was rational? Why wouldn’t be more rational for an Eastern European Jew to go to America and build a new city there?