The Smile That Ended Summer

A Short Story by Barry Germansky

Foreword

One of the hardest things in art—perhaps one of its most profound and necessary subjects—is to confront one’s past and one’s character. To do this honestly, truthfully, and in a way that is also engaging requires an unbinding emotional vulnerability. It means putting oneself out there, ready to be trampled on by the public or praised, and that takes courage. It is rare.

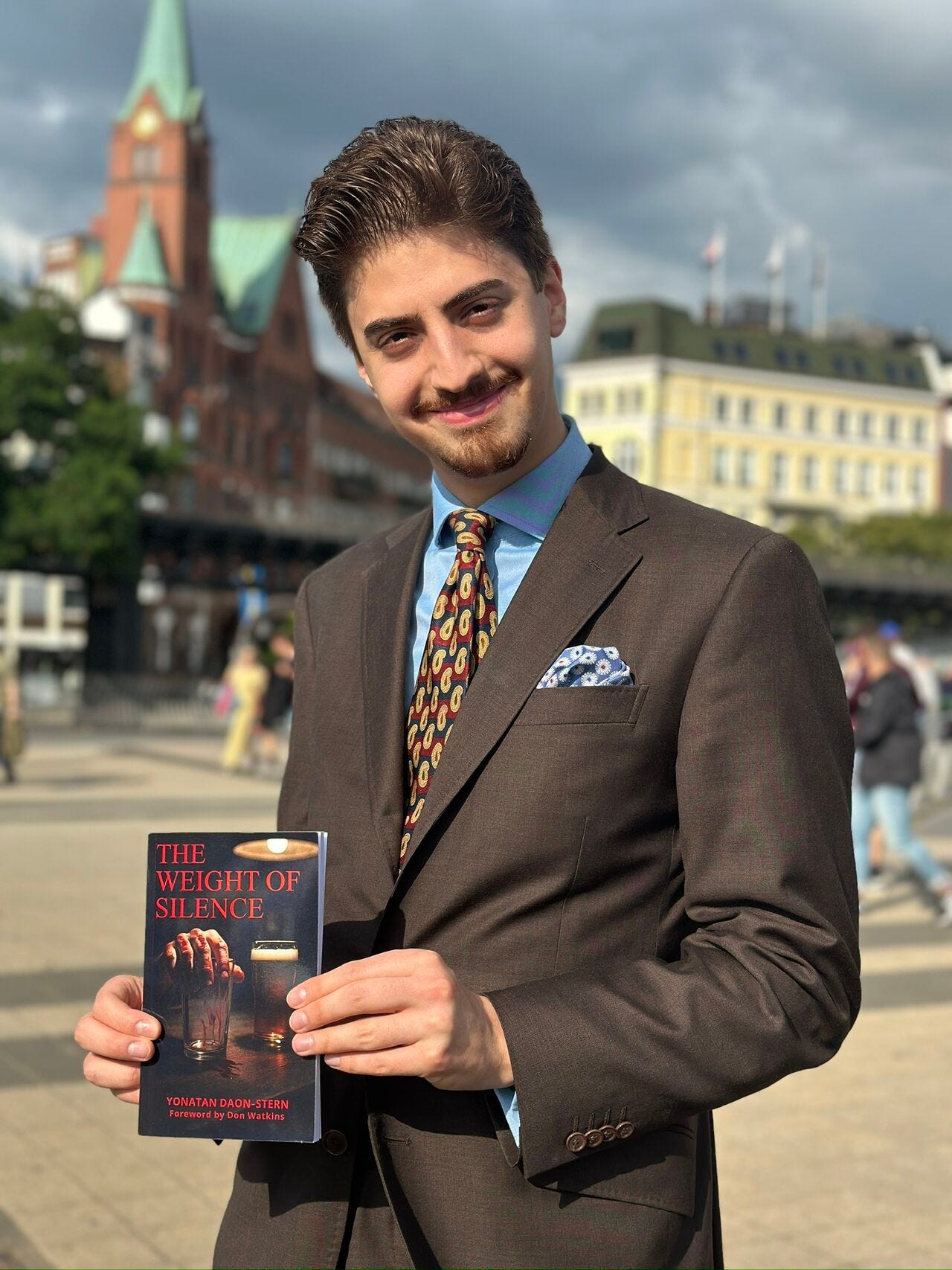

My dear friend Barry Germansky, an established film producer in his own right, is also a prolific writer. He has written many short stories, and I have had the honour of reading through some of them. Many of you will also know his hand already—Barry was the proofreader of The Weight of Silence, my first published work. Out of our collaboration came the idea to publish some of his fiction here on Philosophy: I Need It.

This is a departure from what you, dear readers, are used to: this is not an essay, but a work of fiction. As some of you know, I recently published my first work of fiction, The Weight of Silence, and have shared here occasional pieces of poetry. This new step is part of the larger vision of Philosophy: I Need It—not only as a home for essays on aesthetics or politics, but as a broader aesthetic movement. That movement must also include fiction and poetry.

But beyond these goals, this work stands on its own as a remarkable act of vulnerability. It deals with something few of us dare to revisit: our childhood, our memories, the things we might be ashamed of or reluctant to face, yet which reveal something essential about our character. Barry is not afraid of that wrestling.

It is my honour to present to you “The Smile That Ended Summer”, the first of Barry’s stories to appear here. It is a beautiful piece, and I trust you will find it as moving as I do.

—Yonatan Daon-Stern

August 19, 2025

The Smile That Ended Summer

by Barry Germansky

When I want to remember them, I often find myself dreaming of the pool. Our childhood summers seemed to revolve around that private backyard lagoon, a place less accessible to me now than either of my friends could ever be. One day, when we were twelve, the three of us forgot who we had been for our entire lives up to that point. Life had never asked our permission to change us, and maybe the happy fools of the world are right to pretend that they are life itself and that nobody else matters, that nobody else exists.

I knew true happiness at least once in my life, and I dream of that experience of certainty more often than I’d like to admit. The feeling arrived all at once and without debate on a long hot afternoon in August, when victory – over doubt, over mystery, over expectation – rose without a conscience and told me that my friends were mine and mine alone, that they could exist only insomuch as they kept me attached, by way of an unshakable, unspoken bond, to their every thought and action. I felt so close to them that I couldn’t bear the thought of them possessing independent minds. As long as they did, they also had clandestine opportunities of discovery separate from my own. I couldn’t bear that thought, so it didn’t exist for me as a conscious possibility.

Our interconnectedness was the feeling that came over me, involuntarily and with passionate intensity, when I saw them both floating side by side and clinging onto the edge of the concrete swimming pool with their pruned hands. Their smooth, glistening shoulders were pressed together as they stared at each other and laughed at the giddy electricity in the air. It was a time to believe in happiness.

Robert, whose backyard Ashley and I were visiting, shielded his eyes from the sun with his hand and squinted at me. “Aren’t you coming in the water?”

I thought for a moment. “I don’t think so.”

“Why not?” he asked.

“I don’t know.”

“That’s not an answer!”

“It’s an answer. You just don’t like it.”

Ashley smiled at me, freeing a long strand of her hair from her forehead. “Oh, come on! You might have fun!”

“I’m having plenty of fun already.”

Robert laughed incredulously. “Doing what?”

It was a reasonable question, but not an altogether practical one to answer. I didn’t think practically then. I’ve since convinced myself of the illusion of practicality, at least to the extent that I no longer question whether practicality can be achieved. I couldn’t come up with a practical answer to Robert’s question. I merely wanted to sit and look and hear and think and be – I merely wanted to hold onto that afternoon forever.

But Robert’s question was there, too. Robert’s question! An intruder breaking through the comfort of the afternoon, something that should never have been spoken but was instead spoken as loudly as anything could ever be spoken. I closed my eyes, depriving myself of the wrong sense. I suppose closing my eyes was the most sensible option at the time, as it required less effort than clasping my hands over my ears and shutting out any further disturbances from Robert. I wanted to be at peace with Robert and Ashley. I wanted to stay the way we were – the way we were at that moment – forever.

But Robert was persistent: “Well? What are you doing?”

“I’m thinking.”

Robert smiled the smile of a boy who could still find the fun in anything. “What are you thinking about?”

I knew what I was trying to do, and that was to hold onto the afternoon for as long as possible, to absorb it, to feel it, to become one with it. I wanted to know I was part of that moment in time, that it was real. What I did not know was how I was going to accomplish my mission. I could feel myself, my friends, the pool, the water, the backyard, the sun, the summer, the excitement of all the time I could ever want or need. But I couldn’t feel all these disparate elements at once, and I couldn’t cocoon myself within any temporal space that made sense to me. I couldn’t dispel the notion, the one gnawing at the back of my mind, that maybe this moment, that maybe my entire life, was not any place that I could grasp and store away for later, especially for less desirable times, like the start of a new school year.

This inability to save my euphoric summer afternoon produced an irritating sensation within me, a sensation whose tangible source I couldn’t locate. I opened my eyes for the first time since I had closed them a few moments ago, and the sight of my friends and the pool and everything else around me soothed my inner discomfort until it had all but disappeared.

And then I noticed something that made even less sense to me than my failed attempt at preserving the afternoon: I saw Ashley staring at Robert’s smile. And then I saw what his smile did to her. In a matter of seconds, her lips began to curve themselves upward. Hers was not a smile meant for public consumption. It drew one close, only to push one back. It advertised her knowledge of the joys of secrecy, most notably the blissful things that can be done in such a circumstance.

Robert, who was still smiling and revealing his perfect white teeth that shone with a readiness for adventure, turned to face Ashley, having grown tired of waiting for me to answer his question about the nature of my thoughts. He noticed the same smile on Ashley’s face that I had noticed, and it instantly made its mark on him, transforming his smile into one complementary to hers. His smile had gone from that of a boy filled with the excitement of the infinite possibilities of life to that of a boy who felt the urge to retreat from the world into the solitude he hoped to share with an eager girl.

I now know the full extent of what was lost in that moment of silent conversation, but I knew even at the time that the three of us would never be able to look at one another in the same way ever again. We were no longer the same people. Robert and Ashley had smiled at each other, and I had caught them in the act. We were no longer on equal terms, and there was no longer any possibility for us to become one. We would still keep secrets as a trio, but Robert and Ashley would not invite me to share the secrets they kept between themselves. At the time, I didn’t understand why this breach of our friendship had had to occur, and I’m still unable to formulate an answer.

Over twenty years later, after the deadening promise of adulthood had been fulfilled, I was rushing through the airport of the city all three of us still called home – and still do. I was searching for my terminal when I heard a woman’s voice cry out, “Jack! I don’t believe it!”

I turned around and saw Ashley leaning against a pillar, waving to me. Standing beside her was Robert. I had not seen either of them since high school, and I wasn’t prepared for the grotesque parodies of my childhood friends that proceeded to approach me, carrying their luggage with them. They were still young to a certain extent, but their eyes were full of predigested experience, the kind that other people had presented to them as a trail of breadcrumbs to follow every day of their adult lives.

“It’s been so long!” Ashley exclaimed, but her body language did not match the warmth of her expression. She had stopped her approach about a step too short, a distance that had been subconsciously calculated to prevent an embrace from occurring. Robert had done the same. He did not even attempt to shake my hand. They were strangers to me now, and I was a stranger to them.

We made small talk for a short while, but I don’t remember any of the words we exchanged. At some early point in our short conversation, I noticed a gold band on the ring finger of Ashley’s left hand. As an unfamiliar pain shot through my body, my eyes darted to Robert’s corresponding hand. A gold band, this one slightly different in texture, was waiting for me.

They were married! My friends! The friends I had never wanted to leave behind, the friends whose minds I had wanted to become one with my own. The friends who had disappeared almost entirely from my life during high school and entirely after graduation.

I do not remember seeing them walk away. I was too shocked by the marriage they had kept hidden from me for God knows how long. What I do remember is that the three of us talked without hearing what we were saying to one another. None of us had anything important to say. I remember one thing about that short conversation more than anything else: Robert and Ashley were used to their life together. I am still not used to it now, years after our chance meeting at the airport.

Old memories tend to overwhelm me these days, and I have a habit of inflating their importance. But time, which is infinitely mysterious, does not allow me much else to scrutinize. I think about my two friends at least once a week, and, when I do, I try to forget that scene at the airport. I am usually successful.

The pool returns quite often, though, and it always leads to the same scene. I see all three of us on that afternoon that ended my old sense of self, that ended theirs, too. I see Robert and Ashley floating side by side in the pool that no longer exists. I hear Robert and Ashley asking me to enter the water. I return to the present and feel myself wishing I had. Maybe then I could have prevented Robert from smiling, which would have prevented Ashley from doing the same. Maybe then I could have prevented the smile that ended summer.

If you enjoyed this piece, I encourage you to follow Barry on X @BarryGermansky for more of his work and insights.

Enjoyed this piece?

I’ve just released my debut novella, The Weight of Silence. You can buy it on Amazon.

If you want to support Philosophy I Need It—fiction, essays, and everything in between—consider becoming a monthly member or making a one-time contribution here. Every bit helps me create more and better.

Thank you. Summers long past are well remembered.

Barry, this piece is a quiet triumph. You’ve managed to distill the mystery of memory and the sting of lost innocence into a single, unforgettable moment. What struck me most is how the story lingers after reading - not because of dramatic events, but because of its delicate precision: the pool, the light, the smile, the silence that changes everything.

To fellow readers: take your time with this one. It’s a short story that reads like a memory you’ve half-forgotten from your own childhood. The writing is lyrical without ever losing its clarity, and its emotional weight sneaks up on you. By the end, you realize you’ve been holding your breath.

A story well worth returning to, just as the narrator keeps returning to that August afternoon.