The Real World Howard Roark

The Fountainhead introduced one of the most radical heroes in modern literature. Howard Roark is not heroic because he is charming, successful, or socially admirable. He is heroic because he is internally governed. He acts from a clear hierarchy of values, works with complete focus, and measures his life by the integrity of his creative achievement rather than by approval or applause.

Roark is a fictional figure, but he is not a fantasy. He names a recognisable human type: the individual for whom creative work is not an activity but a necessity, and for whom compromise is not tragic but unthinkable. Such figures are rare in history, rarer still among artists, and rarer still when examined without sentimentality.

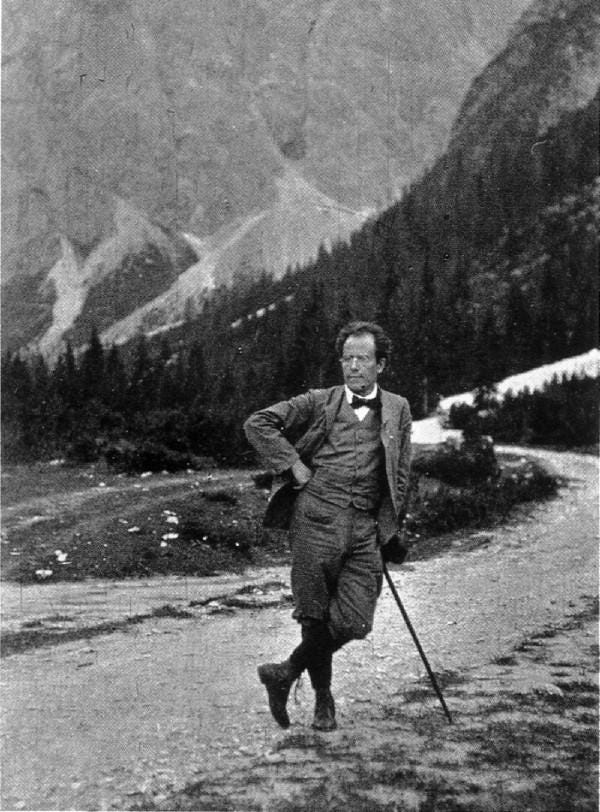

If one looks for historical examples of this Roarkian type, the usual candidates may be political leaders, industrialists, or solitary innovators of the modern age. The most compelling parallel I know belongs elsewhere. It is the composer Gustav Mahler (1860-1911), a figure whose life and work display the same inner law, the same refusal to dilute a vision, and the same willingness to accept isolation as the necessary cost of upholding and accomplishing one’s central purpose.

Creative Vision Over Public Approval

Mahler did not compose in response to taste, expectation, or demand. His music proceeds as if no audience were present at all. From the earliest performances of his symphonies, he was accused of excess, too long, too loud, too grotesque, too emotionally naked. These objections did not surprise him, nor did they alter his course. The works exist because they had to exist, in the form they took, at the scale they demanded. Mahler once said that “a symphony must be like the world. It must contain everything,” and he composed as if this were not a metaphor but a fundamental conviction.

This did not mean Mahler was indifferent to how his work was received. He read reviews, worried over premieres, and felt the sting of incomprehension. But he refused to let that caring alter his compositional decisions. The distinction matters: his integrity lay not in the absence of desire for approval, but in the discipline to compose as if that desire were irrelevant.

This is not the posture of rebellion. Mahler did not seek to provoke, shock, or redefine himself against the present. His was a deeper indifference. Like Roark, he worked according to an inner law and accepted misunderstanding as structural rather than personal. Approval, when it came, was incidental; when it did not, it was irrelevant.

What is striking, in retrospect, is not that Mahler misunderstood his audience but that he never attempted to correct the mismatch. He made no aesthetic concessions to frequency of performance, critical fashion, or institutional comfort. The symphonies grew ever larger, more complex, more uncompromising, as if the distance between his inner necessity and the world around him could only widen.

If one needs a single example of how radical this inner necessity could be, the Third Symphony is enough. It is almost two hours long, written for a huge orchestra, children’s choir, women’s chorus, and alto soloist. It unfolds over six movements, each one turning its attention to a different rank of existence, nature, life, man, the angels, before arriving at a final answer: that love is the highest value and the deepest power in the world. Nothing in the symphonic repertoire before it looks like this. No patron, no audience, no tradition ever demanded such a work. No one said, “We must have a symphony that does this, here’s a government grant.” It exists because one man’s vision required it.

It is one of the most radically first-handed acts of composition in history. And it is not an exception. In different ways, each of Mahler’s symphonies is like this: unmistakably personal, uncompromisingly individual, and written as if there were no authority higher than the truth of what he had to say.

Mahler’s confidence was not psychological bravado. It was the quiet certainty of someone answering to a standard that does not consult others. One hears in this not defiance, but inevitability, the sense that the work unfolds because there is no legitimate alternative.

Loyalty to Form, Not Fashion

Mahler is often described as a breaker of traditions, a composer standing at the threshold of modernism, the last of the romantics. Howard Roark is described similarly. In both cases, the phrase gets cause and effect backwards.

Roark does not set out to overthrow architecture. He rejects inherited forms only when they have become dishonest, decorative shells emptied of purpose. What he builds looks radical because it grows from a stricter fidelity to structure, material, and function than his profession is willing to tolerate. Tradition breaks against him because it has already hollowed itself out.

Mahler belongs to this same category. He does not abandon the symphony or attack it from the outside. His famous remark that “tradition is not the worship of ashes, but the preservation of fire” is often quoted for good reason: what he inherited from the symphonic past was not its surface, but its flame. The length, the density, the sudden breaks and juxtapositions were not conceived as shock tactics. They are what happens when a composer asks the symphony to tell the truth about a modern inner life, and refuses to abridge the answer.

This is a different kind of radicalism from the fashionable one. Mahler’s symphonies do not announce a break with the past; they carry the past forward until its sentimentalities and evasions can no longer survive. Roark and Mahler both stand at the point where tradition, confronted with integrity, either deepens or shatters. Neither man chases the new. The new is simply what remains once the false has been removed.

Solitude Without Theatrics

A figure like this does not stand in the middle of his time. He stands slightly apart from it. Both Roark and Mahler move through worlds in which they are necessary and never quite at home.

Mahler repeatedly removed himself to Alpine solitude to compose. The image is not romantic but practical: long days, isolation, a landscape stripped of distraction, and a mind left alone with the demands of the work. The symphony, for Mahler, is not a collective negotiation or a cultural compromise. It is the product of a single consciousness ordering vast material according to its own inner necessity.

Roark works under similar conditions. His buildings are not the result of committee thinking or social conversation. They are conceived as unified forms, each element answering to the logic of the whole. A Roark building, like a Mahler symphony, is unmistakably the work of one mind. Not improvisational, not consensus-driven, but integrated from foundation to final detail.

What separates solitude here from isolation is purpose. Mahler does not withdraw in order to escape the world, but in order to return to it with something whole. The mountain hut serves the same function as Roark’s drafting table: a place where the noise of opinion dissolves and only the requirements of the work remain.

Neither man turns this solitude into a mythology of suffering. It is not cultivated as an identity. It is simply the condition required for undiluted creation. When the work is finished, both re-enter the public sphere, knowing it may resist or misunderstand what they bring, and accepting that fact without complaint.

Integrity Without Compromise

Mahler’s unwillingness to compromise was not confined to composition. It governed his entire professional life, most visibly in his work as a conductor. On the podium, he demanded absolute fidelity to the score and total seriousness from the musicians under him. Interpretive shortcuts, routine, or convenience were intolerable. Rehearsals were relentless. Standards were non-negotiable.

This posture earned him results and enemies. Under Mahler’s leadership, the Vienna Court Opera reached an extraordinary level of artistic excellence and coherence. Standards were raised across the board, rehearsals intensified, discipline tightened, and the repertoire was treated with a seriousness it had not known before. The institution flourished precisely because Mahler refused to treat art as an administrative routine.

At the same time, hostility accumulated. Mahler did not cultivate conflict, but he accepted it as the price of refusing to dilute his demands for the sake of harmony. Institutions value smooth functioning; Mahler valued truth to the work. Where it came into conflict, he chose the work every time. The friction was inevitable.

Here, the parallel with Roark becomes quite exact. Roark does not compromise because compromise is not a practical adjustment; it is a moral failure. To alter a design for approval is to abdicate authorship. Mahler holds the same principle, whether composing alone or standing before an orchestra. The music comes first, and everyone involved must rise to it, or step aside.

Solitude follows naturally from this position, but it is not the core of it. The core is integrity: the refusal to falsify a vision in order to make it easier for others to accept. Mahler’s Alpine retreats serve that integrity, but the same stance appears publicly, under pressure, in rehearsal rooms and opera houses, where the cost is social conflict rather than quiet isolation.

That cost was real. Mahler accumulated adversaries not because he provoked them, but because he would not accommodate mediocrity. Like Roark, he understood that enemies are not chosen; they emerge where standards meet resistance. The refusal to compromise does not guarantee isolation, but it makes it an ever-present possibility.

It would be a mistake to imagine that this integrity required withdrawal from institutions. Mahler understood exactly how much authority was required simply to make his work possible. His positions in Hamburg, Vienna, and later New York were not concessions but strategic necessities. Without his reputation as a formidable and respected musical director, it is unlikely that his symphonies would have been performed at all. Even with that authority, they were greeted with hesitation, resistance, and often open hostility.

Ken Russell’s film Mahler crystallises this hierarchy in a single exchange. When a journalist asks Mahler whether he considers himself a composer or a conductor, he replies: “I conduct to live; I live to compose.” The line is fictional, but the order it establishes is exact. Conducting is survival. Composition is purpose.

Roark articulates the same principle in The Fountainhead, insisting that he does not build in order to have clients, but has clients in order to build. In both cases, institutions are not authorities to be appeased but instruments to be used, necessary, demanding, and never confused with the work itself.

Mahler’s standing made the premieres possible. It protected the work long enough for it to be heard. Without that standing, the symphonies might not have failed; they might never have existed publicly at all. His independence did not float above institutions; it moved through them, using their weight to bring into the world works no institution would have asked for on its own.

The same logic applies to Roark. He studies, apprentices, and works within architectural firms not because he accepts their authority, but because mastery of the field is a prerequisite for independent creation. Institutions provide access and skill; they do not confer permission. What endures, in both cases, is not what was done on their terms, but what was created once the authorship remained undiluted.

Enemies as Consequence, Not Strategy

Neither Roark’s buildings nor Mahler’s symphonies are acts of spite. They are not shaped in reaction to resistance, criticism, or hostility. The naysayers do not enter the creative calculation at all. This is made explicit in one of the novel’s most devastating moments, when the villain, Ellsworth Toohey, having failed to break Roark, asks him what he thinks of him. Roark answers simply: “But I don’t think of you.”

This is not a gesture of contempt, but an expression of complete independence. Toohey is irrelevant to the act of building. His hostility has no creative significance. Roark’s work proceeds without reference to its enemies because it answers to a standard that does not consult them.

Mahler occupies the same position. His symphonies do not argue with objections; they ignore them. Their scale, intensity, and formal ambition are not defensive manoeuvres or aesthetic provocations. They are the natural outcome of a non-compromising mind following an inner necessity to its full conclusion. Like Roark, Mahler does not create against opposition. He creates as if opposition were beside the point.

It is precisely this posture that generates enemies. Institutions built on accommodation experience non-negotiable standards as a threat. People who expect compromise read indifference as arrogance. Yet the conflict is secondary. Neither Roark nor Mahler derives meaning from antagonism. The work is not a reply; it is a statement.

In the end, this stance explains both their victory and their immortality. Because they never built in reaction to the present moment, their work outlived it. What survives is not a record of struggle, but an intact vision, buildings and symphonies that remain whole because they were never bent. The refusal to compromise did not merely preserve their integrity; it ensured that what they created would endure beyond the noise that once surrounded it.

Friendship With Standards: Bruno Walter & Steven Mallory

Non-compromise is often mistaken for misanthropy. In reality, it creates the conditions for a very precise and demanding kind of friendship. Both Roark and Mahler are incapable of generosity toward the unearned, but once genuine value is recognised, their loyalty is unwavering.

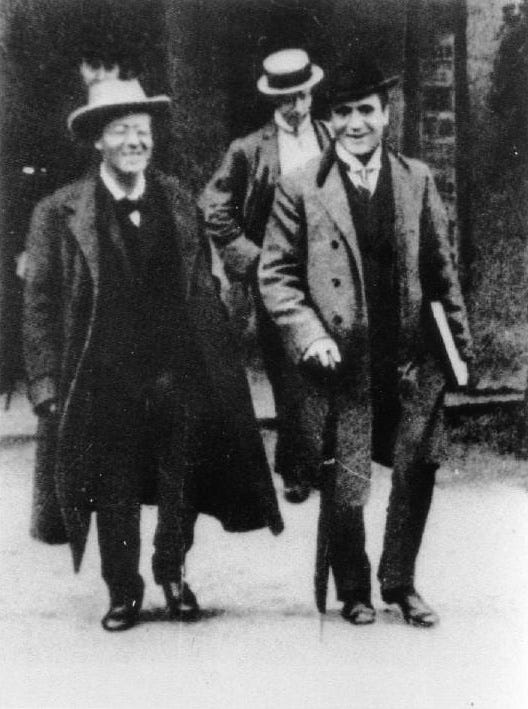

Bruno Walter first came to Mahler after hearing his First Symphony when he was 18. At a time when very few people understood what Mahler was doing, the young Walter recognised something singular in that music and sought him out. Mahler, in turn, immediately recognised Walter’s seriousness, musical intelligence, and integrity. What followed was not an act of charity, but an exchange grounded in judgment. Each saw value in the other and responded accordingly.

Mahler took Walter under his wing in the fullest sense. He mentored him for more than a decade, helped him secure positions, entrusted him with real responsibility far earlier than most conductors would have received it, and stood behind him when opposition arose. At moments when Walter struggled financially, Mahler quietly sent him money, not as compassion for weakness, but as practical support for something he knew was worth preserving and developing.

What makes the relationship extraordinary is both its duration and its symmetry. Mahler did not withdraw his support once Walter began to succeed, nor did he grow threatened by his growing authority. He treated him as a bearer of the same standards. And in time, Walter became one of the principal carriers of Mahler’s music, bringing the symphonies to audiences across Europe and later the wider world, preserving them at a moment when their survival was far from guaranteed. This was not gratitude returned; it was recognition fulfilled.

The Fountainhead offers several examples of Roark’s selective loyalty, but the clearest is Steven Mallory, the sculptor. Mallory is crushed by a culture hostile to integrity, yet Roark recognises the absolute honesty of his work immediately. His response is not pity or encouragement, but sustained belief translated into action. Roark stands by Mallory not because Mallory needs him, but because Mallory’s work deserves to continue.

In both cases, the relationship is mutually beneficial without being transactional. Mahler needed Walter as much as Walter needed Mahler, not emotionally, but structurally. The same is true of Roark and Mallory. Integrity recognises integrity, and when it does, loyalty follows naturally.

What Remains

Seen in this light, Mahler’s friendships do not soften his severity; they complete it. The same principles that made him uncompromising also made his alliances durable. Standards, once fixed, govern everything: the work, the collaboration, and the legacy that survives both.

Howard Roark is a fictional construct; Gustav Mahler is a historical man. The distance between them matters. A novel can present an ideal without remainder; a life never can. Yet the point of a literary archetype is precisely that, once named, it allows us to recognise certain patterns in reality with greater clarity.

Mahler fits that pattern more closely than most. He was a man who worked according to an inner law, who refused to falsify his vision for the sake of approval, who accepted enemies as the cost of standards, and who reserved his deepest loyalty for the few minds he judged as serious as his own. The symphonies and the buildings grow out of the same posture: a conviction that the work must remain whole, even if the world around it does not.

There was a price. Mahler drove himself with a ferocity that may well have shortened his life. The intensity, the overwork, the refusal to ease off even when his health was failing; these are not incidental details. They raise an uncomfortable question: perhaps this is simply what such a life demands. Perhaps there is no gentler way to bring into existence works on that scale, with that level of inner honesty.

While we don’t have the opportunity to speak with Mahler or Roark directly about their challenges, we can immerse ourselves in their incredible work. So, let’s celebrate their genius by listening to a beloved Mahler symphony or diving into our favourite passage from The Fountainhead.

To a year of uncompromising, epic and beautiful work.

Merry Christmas and Happy New Year!

-Yonatan

If you enjoyed Philosophy: I Need It, and want to see more, you can support my work by buying me a coffee. Every contribution makes a real difference. Thank you!

One of my favourites is the 4th movement of the 4th Symphony: Wir geniessen die Himmlischen Freuden (We enjoy the heavenly pleasures). It is so full of joy and beauty. A good place to start (in my opinion) if you are new to Mahler's music.

We so desperately need people like you. I will become a founding member soon. Never stop the work you do.