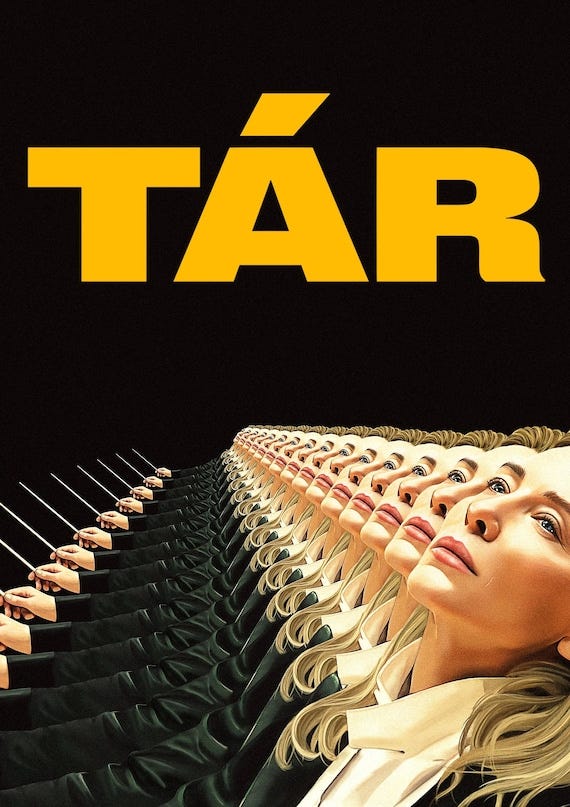

TÁR: A Symphony Without A Soul

I don’t usually write film reviews. But TÁR left me deeply frustrated—not because it challenged me, but because it hollowed out something I care about. This is a film praised as high art, as profound and intellectual. But beneath the surface, it’s emotionally barren and spiritually corrosive.

Spoiler Alert: This review contains detailed discussion of the film’s plot and ending.

The plot follows Lydia Tár, a world-famous conductor and composer at the height of her career, preparing to record Mahler’s Fifth Symphony with the Berlin Philharmonic.

She’s intelligent, articulate, and commands respect. Early on, she even delivers a strong defence of artistic greatness, confronting a student at Juilliard who refuses to play Bach for “identity” reasons. In that moment, she speaks for the music. She speaks for standards. She speaks, it seems, for what art should be.

But then the mask begins to slip.

We learn that Lydia Tár is vindictive, petty, and cruel. She blocks a young conductor’s career out of personal spite. She refuses to promote her loyal assistant to preserve her power. She plays loud music to sabotage a neighbour’s apartment sale. She threatens a child—literally threatens to kill her, in a scary German accent. She spirals. By the end, she’s not just flawed—she’s toxic.

And here’s the kicker: she’s supposedly a student of Leonard Bernstein.

That detail alone breaks something in the film. Bernstein was known for his warmth, charisma, and depth—a man who loved music and humanity. How could he have nurtured someone like this? The contrast is jarring. Lydia Tár is all control, no soul. All fear, no reverence. A character who embodies everything wrong with the way our culture now views power, art, and excellence.

And yes—if someone in real life behaves like this, they absolutely should lose their position. Morally speaking, consequences matter. But that’s not the issue.

The problem is that TÁR refuses to separate the person from the art. It doesn’t allow for the possibility that Mahler’s Fifth might still mean something even if the conductor is monstrous. It collapses the distinction between judging someone as a public figure and judging the work they produce. In the same way that the Juilliard student wants to cancel Bach, the film asks us to do the same with Lydia Tár.

We can hold people accountable. But when it comes to art, we judge the work. That’s the line the film erases—and in doing so, it joins the very forces of cultural nihilism it briefly seems to critique.

And all of this takes place in a world portrayed as joyless, sterile, and lifeless. Berlin, in this film, is cold and grey. The institutions are hollow. The people disconnected. Even the ghostly visions and strange side scenes—like a dying neighbour or a mysterious thud in the night—don’t add depth. They reinforce the bleakness.

To be clear, TÁR is not a poorly made film. It’s well crafted and beautifully shot. Cate Blanchett’s performance is remarkable in its control and realism. Every scene feels believable, even immersive. That’s partly why the experience is so disturbing. The film does its job so well, technically, that its moral and philosophical void hits even harder.

What’s most painful is how the film pretends to be about Mahler’s Fifth. It builds toward that moment, teases it constantly. And in the end, what do we get? A single, hollow gesture: the opening trumpet notes of the first movement—the funeral march. That’s where her story ends. She hears the music begin, then violently breaks, attacking the bland, soulless clone of a conductor who has replaced her. The impostor who stole her score. The one who now gets to conduct the full symphony.

He gets the triumph. He gets the Adagietto. He gets the final victory. She gets the funeral.

It tries to build toward the transcendence of Mahler’s Fifth, but it ends in collapse, like a bad imitation of the Sixth. Except the Sixth is profound, tragic, and sublime. TÁR isn’t. It’s just bleak. No struggle, no heroism, no meaning—only defeat.

And then she loses everything. Her job. Her orchestra. Her family. Her child. Her home. Her music. She’s exiled—culturally and geographically—reduced to conducting a video game score in the Philippines for an audience of cosplayers. The great defender of Mahler ends up surrounded by plastic swords and fantasy helmets.

Justice, the film says. The system works. The message is clear: cancel culture is not only effective—it’s correct. The fall is complete. And the art? Forgotten.

TÁR isn’t a film about music. It’s a film about the futility of music. It uses high art as a backdrop for its cynicism and nihilism. It strips away beauty, transcendence, and the meaning of greatness, only to say: none of it matters. What matters is that she was flawed. So she must fall.

The experience is also draining—not just emotionally, but physically. At over two and a half hours, the film asks us to sit with this cold, joyless spiral for far too long. It offers no arc of redemption, no glimpse of grace, not even a philosophical point to justify its bleakness.

The darkness here isn’t tragic—it’s nihilistic. It doesn’t reveal the human condition, it just wallows in it. We’re left watching a bad person unravel, with nothing to learn except that greatness is an illusion and the world is empty. If that’s the message, what exactly are we celebrating? Why are we wasting our time watching this?

This film doesn’t just misunderstand Mahler. It misunderstands why we need Mahler. Why we need art. Why we need to elevate the human spirit.

TÁR is a well-crafted insult to music, to greatness, to the human soul. It pretends to explore transcendence, but delivers only decay.

Don’t watch it. Not because it’s boring; it’s not.

Don’t watch it because it’s bad for the soul. If you love music, if you believe in the possibility of greatness, if you look to art for meaning, this film will offer you none. It only takes.

For me, this is a 3/10.

Not because it’s poorly made, but because it knows what greatness is and chooses to spit on it.

If you enjoy this kind of content—longer reflections on films from a philosophical perspective—let me know in the comments. I’d love to hear your thoughts, especially if you disagree.

If you enjoyed Philosophy: I Need It, and want to see more, you can support my work by buying me a coffee. Every contribution makes a real difference. Thank you!

I haven't seen this movie but I'd certainly value your thoughts on others.

Thanks for a good piece, Yonatan. I saw Tar when it came out and was incredibly disappointed, mostly because it purports to be about classical music and artistic creation and yet manages to be completely devoid of any joy in these fundamentally life-affirming things. Mahler is sublime, and it would have been so easy to project some of the beauty of his music and the delight of creating and experiencing it. Yet the film's soul was barren.