Our Trains Move Faster, But Where Are We Heading?

An Essay on Travel, Time, and the Transformation of Culture

I. The Orient Express

A middle-aged Parisian sits alone in his private cabin in a dark three-piece suit. The champagne in his glass trembles gently in accordance with the train’s rhythm. Mahogany panels embrace him; their polished glow is only broken by the glint of brass lamps swaying with each curve of track. Outside, the Alps rise like a painted landscape; peaks dusted with snow, valleys cut by rivers that flash silver in the morning sun.

He cannot possibly hear them, and yet, he hears them. The cowbells of distant pastures ring in his imagination, completing the scene beyond the glass. The train orchestrates it: the hum of wheels against steel as a bass line, the whistle as a clarinet, and the invisible bells chiming in counterpoint.

He sleeps soundly through the night, undisturbed. The bed is firm but forgiving, the sheets cool, and the air is touched with coal and mountain pine. He wakes not dishevelled but restored, as if the very act of travelling has refined him. The Orient Express has not carried him through the Alps; it has carried him into a new self.

By the time the train exhales at Vienna’s station, the transition is complete. He steps down not as a tired traveller but as a man perfectly attuned. His shoes click in rhythm with the tram bells outside. He knows where to go, as if the city has been preparing for him. Within minutes, he is seated in Café Central, the marble tabletop cool under his hands, the coffee arriving without a word, dark, strong, dignified. The air is alive with the rustle of newspapers, the scratch of pens, and the low murmur of ideas exchanged.

This was never just Paris to Vienna. The train has transposed him, like a symphonic modulation from one key to another. From croissant to strudel, from chanson to waltz, from one civilisation to the next. The train itself has set the tempo, tuned the ear, and softened the heart so that when he arrives, he is already Viennese.

This was what travel used to be like, not merely a means of transport, but a gesture of civilisation itself. The Orient Express was not an anomaly; it was the natural expression of an age that believed in continuity, in refinement, in the quiet majesty of progress. To recline in a mahogany carriage and wake rested beneath the shadow of the Alps was of a piece with stepping into a Viennese café where marble tables bore witness to conversations as enduring as the architecture around them.

Life in Vienna at the turn of the century unfolded at a different pace. Time moved with a measured rhythm, steady and unhurried, as though time itself had more patience. People did not live under the shadow of catastrophe or disruption; they trusted in continuity, in the small securities of daily life. To walk the streets was to feel surrounded by a quiet permanence, by gestures and habits that assumed tomorrow would be much like today.

Stefan Zweig in The World of Yesterday captured that atmosphere beautifully:

“They walked slowly, they spoke with measured accent, and, in their conversation, stroked their well-kept beards which often had already turned gray. But gray hair was merely a new sign of dignity, and a ‘sedate’ man consciously avoided the gestures and high spirits of youth as being unseemly. Even in my earliest childhood, when my father was not yet forty, I cannot recall ever having seen him run up or down the stairs, or ever doing anything in a visibly hasty fashion. Speed was not only thought to be unrefined, but indeed was considered unnecessary, for in that stabilized bourgeois world with its countless little securities, well palisaded on all sides, nothing unexpected ever occurred.”

This is the rhythm of life that gave birth to the Orient Express: a tempo not of haste, but of dignity. Travel was not a disruption to life but an extension of it, woven with the same patience, the same confidence, the same belief that beauty and serenity were the natural order of things.

Vienna, especially, carried this atmosphere in its very stones. To walk its boulevards was to feel surrounded by an order that had been built to last, opera houses and museums as expressions of a people confident in their destiny. In the cafés, the hum of newspapers being unfolded, the scratch of pens across paper, the quiet clink of porcelain: all of it formed a rhythm as steady as the Orient Express itself. Here, one lived well, and easily, and without cares. The motto was simple: live and let live.

The Orient Express belonged to this world. Its mahogany panels, its linen and crystal, its carefully measured serenity, these were not indulgences, but declarations of faith in civilisation. Each journey was a reaffirmation of man’s power to shape life into something worthy, ordered, beautiful. To travel from Paris to Vienna was not just to move between cities; it was to be carried along a current of culture, to be transposed from one key to another in Europe’s great symphony.

II. The Flixtrain

A man stands in his flat, suitcase open on the bed. He is not deciding which tie best suits the marble light of Café Central, but how many shirts he can take before the scale at the airport flashes red. Not indulgence, not abundance, but maximum suitcase weight. As if there were some precise number that could define how much of Vienna he is permitted to carry with him.

He folds his trousers with anxiety, measuring them against the limit. He thinks not of champagne in crystal, but of plastic cups. Not of sleeping soundly to the rhythm of steel and mountain wind, but of a seat where his knees press against the row ahead. A place not of rest but of endurance.

At the airport, he arrives three hours early, not for leisure but for inspection. He queues among the anxious, shuffling forward beneath fluorescent light. Belts off, shoes off, liquids measured into plastic bags. His name is not spoken as a welcome but shouted as a boarding group. He moves not with dignity but in a herd, funnelled toward gates like cattle toward pens.

And when at last the plane lifts, there is no civilizational transition, no symphonic modulation from croissant to strudel. There is only the hiss of recycled air and the hum of jet engines. He does not hear cowbells in the mountains below, though they are there. He cannot. He is sealed off from the world he crosses, not carried into it.

It hasn’t been more than a month,

and yet I return to the old continent.

To dear Vienna, of all places…The words rise in his mind,

but they taste different now.What once was a promise of beauty

has become a reminder of loss.

This is what Europe has become.We lost the Orient Express,

we gained the Flixtrain.You arrange travel to Vienna,

but you don’t know what it means to arrive.

III. What Happened?

This was the world the Orient Express both served and embodied—a civilisation that seemed as permanent as the mountains it crossed. The immediate answer is obvious: the wars. The mass slaughter that began in 1914 shattered the world Zweig remembered. But even that did not bring the Orient Express, or the Europe it embodied, to an instant halt. It did not vanish overnight. It faded over decades.

Zweig recalled what it meant to be young in Vienna:

“To have seen Gustav Mahler on the street was an event that we proudly reported to our comrades the next morning as a personal triumph; and when as a boy I was once introduced to Johannes Brahms and he patted me on the shoulder in a friendly fashion, I was dazed for some days after by the astonishing experience.”

This was the measure of reverence: a glimpse of Mahler was a triumph; a pat on the shoulder from Brahms was a life-marking event. Greatness in art was not an ornament of culture—it was the axis around which culture turned. The young aspired not to Instagram influencship but to proximity with genius. Beauty and thought were the currency of admiration.

The decades that followed still carried the echo. In the 1920s, the carriages were polished, the linens pressed, and the timetables still engraved with elegance. In the 40s and 50s, men still wore hats and ties, and women still travelled with care and ceremony. One could still walk into a café in Vienna and find marble tables, newspapers on wooden wands, and the ritual of service intact. The aesthetic instinct had not died.

Yet underneath, the foundations were cracking. The 19th century regarded beauty as essential, not optional. Art was part of everyday life; symphonies and paintings were not luxuries for a few, but the air the culture breathed. Vienna, especially, was a city of living art, where people expected life itself to have form, harmony, refinement. The Orient Express was simply one manifestation of that wider ethos.

From the Renaissance domes to the boulevards of Haussmann, from Raphael to Bouguereau, beauty was treated as essential to life itself. The Orient Express was one continuation of that lineage. What followed was not only the decline of beauty, but the enthronement of its opposite.

Step by step, decade by decade, that conviction dissolved. First came relativism in philosophy: the denial of truth, the sneer at certainty. Then in art: from Bouguereau to Pollock, from harmony to disintegration, from beauty to noise. Each decade loosened the standard a little more, the tie less formal, the ritual less precise, the seriousness less secure.

By the 1960s, the revolt was complete. The hippie counterculture made its declaration: beauty itself was the enemy. Woodstock was not indifferent to beauty; it was a declaration of war against it. Torn jeans, muddy fields, unwashed hair, these were not accidents but signals. They announced a philosophy that viewed beauty not as a human birthright, but as an illusion to be dismantled. What had once been signs of neglect were now recast as badges of freedom. Mud was purity, noise was honesty, chaos was truth. In this reversal, the irrational itself was enthroned as the new aesthetic ideal. And once the irrational was praised, beauty had no defence left; it could only be mocked as oppressive or false.

That is the deeper tragedy. We did not simply drift away from beauty into neglect. We began to embrace its opposite. What the 19th century saw as essential, beauty as the affirmation of life, the modern age derides as kitsch, elitist, or oppressive. In its place, it elevates the crude, the formless, the casual, and the ugly. To reject refinement is now a posture of virtue. To destroy beauty is now an act of rebellion.

The fade-out was not passive. It was active. It was a retreat from the conviction that life deserves to be celebrated and, finally, an attack on that very idea. And this is the world in which the Orient Express became impossible and the Flixtrain inevitable.

IV. The Ersatz

What has replaced the Orient Express is not merely a different train but a different morality. It is called Flixtrain. Its colour is green, but not the green of spring or of life. It is the green of sermon, the green of obligation, the green that tells you you should feel virtuous for enduring less. Its promise is simple: cheap, efficient, good enough.

Inside, the world has been stripped to plastic and laminate. Seats are narrow, and the fabrics are already worn out. There is no memory here, no detail to cherish, no hospitality gesture that lingers in the mind. The interiors are designed to be forgotten, because forgetting is the point. Travel is no longer meant to elevate you; it is meant to process you.

Even the passengers have changed. Once, men wore three-piece suits, and women wore hats and gloves, not from vanity, but from a recognition that travel itself was a ceremony. Now the carriages fill with hoodies, sneakers, and earbuds, bodies slouched as if apologising for their own presence. The attire matches the train: casual, disposable, stripped of all ambition to be beautiful.

The exchange is plain: once, Europe built trains that said, make it worthy of man. Now it builds trains that say, make it barely tolerable. The civilisational gesture has inverted itself. We move more quickly, but with less meaning. Our trains move faster; our civilisation moves backwards.

V. Aesthetics Is Not a Luxury

The real loss is not the train itself, but the very belief that beauty is a part of life.

To call beauty a luxury is already to betray it.

Beauty is not an accessory, not frosting on the cake of “real life.” Beauty is a necessity. It is spiritual fuel. It gives us the strength to rise above routine, to see our lives as worthy, to take ourselves seriously. We are not machines to be fed only efficiency and function. We are human beings, and we need inspiration, grandeur, and delight. Without them, life shrinks.

The Orient Express was one form of this necessity, but not the only one. I do not mean that we must rebuild it exactly as it was or copy the past in order to recover what was lost. To do so would be a parody of beauty, not its rejuvenation. We must innovate; we must find new forms, new expressions, and new ways of designing travel, buildings, cities, clothes, and even the most minor details of our environment, but always with one criterion at the forefront: is it beautiful?

For beauty changes us. It makes us better people. It raises our mood, sharpens our dignity, lifts us into seriousness, and makes us treat the world with reverence instead of carelessness. To step into a beautiful place is to be reminded that life is not merely to be endured but celebrated.

That is why the Orient Express mattered. Not because it was extravagant, but because it carried a message written in mahogany and crystal: your life is worth this. And that is what we must recover today, not the nostalgia, not the pastiche, but the principle. The principle that beauty is as necessary to human flourishing as food or shelter.

Art is not optional. Beauty is not a lecture. It is life’s permission slip, its command: live as though you are worthy.

VI. Beautify Everything

We must not be content to mourn what was lost. Mourning alone is paralysis. The Orient Express teaches us a principle that has not aged: that even the most mundane act, travel, dining, or rest, can be elevated into a civilisational gesture when it is shaped by beauty. That principle must be reborn, not as imitation, but as creation.

We can build it again, in new forms, with new ingenuity. Imagine trains designed not for disposability but for dignity: quiet, spacious, and made of materials that age with grace. Imagine a service that remembers your name, rituals that turn a journey into an experience, dining cars that feel like salons, menus printed with care, glass instead of plastic, and space for reverence instead of hurry. Imagine beauty without guilt, where the pinnacle is allowed to exist and, in existing, pulls the whole curve upward.

And let it not stop at the train. Let the concert hall, the hotel, the café, the boulevard all stand as allies in the same cultural mission: to remind us that human life deserves magnificence. Every second we spend on this earth should be worthy of us. We need beauty as we need food and air. It inspires us, sharpens us, and ennobles us. It makes life not only bearable but radiant.

Picture it: you step out from the fluorescent concourse into a carriage of calm light and wood. Time slows. The world feels worthy again. The mountains pass, and you hear, not the hiss of earbuds, but the tremolo of strings, a civilisation that still believes in itself. A porter greets you by name. The moment is whole. The moment is beautiful.

Do not apologise for beauty.

Demand it.

Create it.

Live as if every detail matters—because it does.

Let us be dazed again by excellence, as a child once was by the touch of Brahms. Let us seek greatness relentlessly—in our work, in our loves, in our homes, in the clothes we wear, in how we eat, and in how we travel. There cannot be greatness without beauty. The ugly can never be great.

So let us not rebuild, but build.

Build anew. Build higher.

Build beautifully.

Beautify everything.

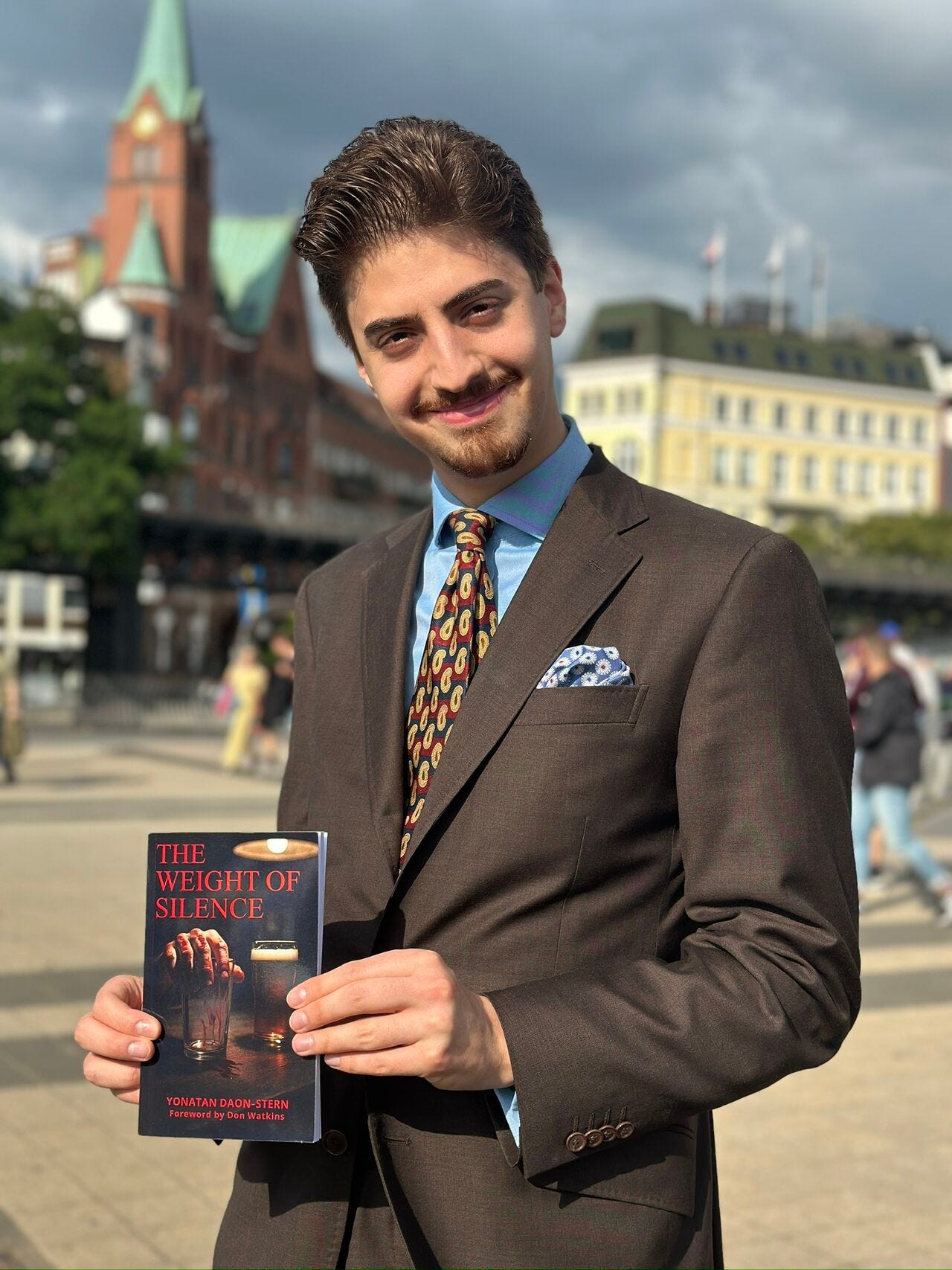

Enjoyed this piece?

I’ve just released my debut novella, The Weight of Silence. You can buy it on Amazon.

If you want to support Philosophy I Need It—fiction, essays, and everything in between—consider becoming a monthly member or making a one-time contribution here. Every bit helps me create more and better.

I always remember my boss’s advice when I was a kid. He said, “work like a gentleman”.

It took many years for me to understand the importance of his words.

Thank you for your work.

It's pieces like this that are rare spiritual fuel in a world increasingly devoid of it.