My Experience From The Caspar David Friedrich 250th Anniversary Exhibition

It wasn’t my first pilgrimage to the capital of Northern European romanticism. Last year, around the same time, I took a special excursion to the Hamburger Kunsthalle just to see “The Wanderer” for the first time with my own eyes and returned to Frankfurt the same day.

Indeed, this also wasn’t my first concurrent encounter with many of Caspar David Friedrich’s works. In October and November of 2023, I happened to be in Switzerland, enabling me to visit the smaller prelude exhibition displayed in the Winterthur Art Museum. There, I saw a lot of the greatest Friedrich paintings alongside The Wanderer, of course. This gave me more perspective. That exhibition also contained many works by Friedrich’s contemporaries, such as Johan Christian Dahl, Carl Gustav Carus, and many others.

So when I came to the massive 250th anniversary exhibition in Hamburg, I thought I was well prepared. Nevertheless, I was still blown away.

The exhibition was full, which was rather annoying. It was impossible to become intimate with many of the paintings, especially the big ones, but I wasn’t too bothered by that, considering that I managed to see most of the big ones in the previous encounters I’d had with Friedrich. Besides, I was very happy that so many people would flock in to see this 200+ year-old art. That was indeed a very positive sign.

The fact that I’ve had most of the artist’s oeuvre laid out in front of me has enabled me to appreciate the grandeur of his life achievement. This added context also enabled me to clearly see the general overlapping themes in most of his work.

Let us dive in.

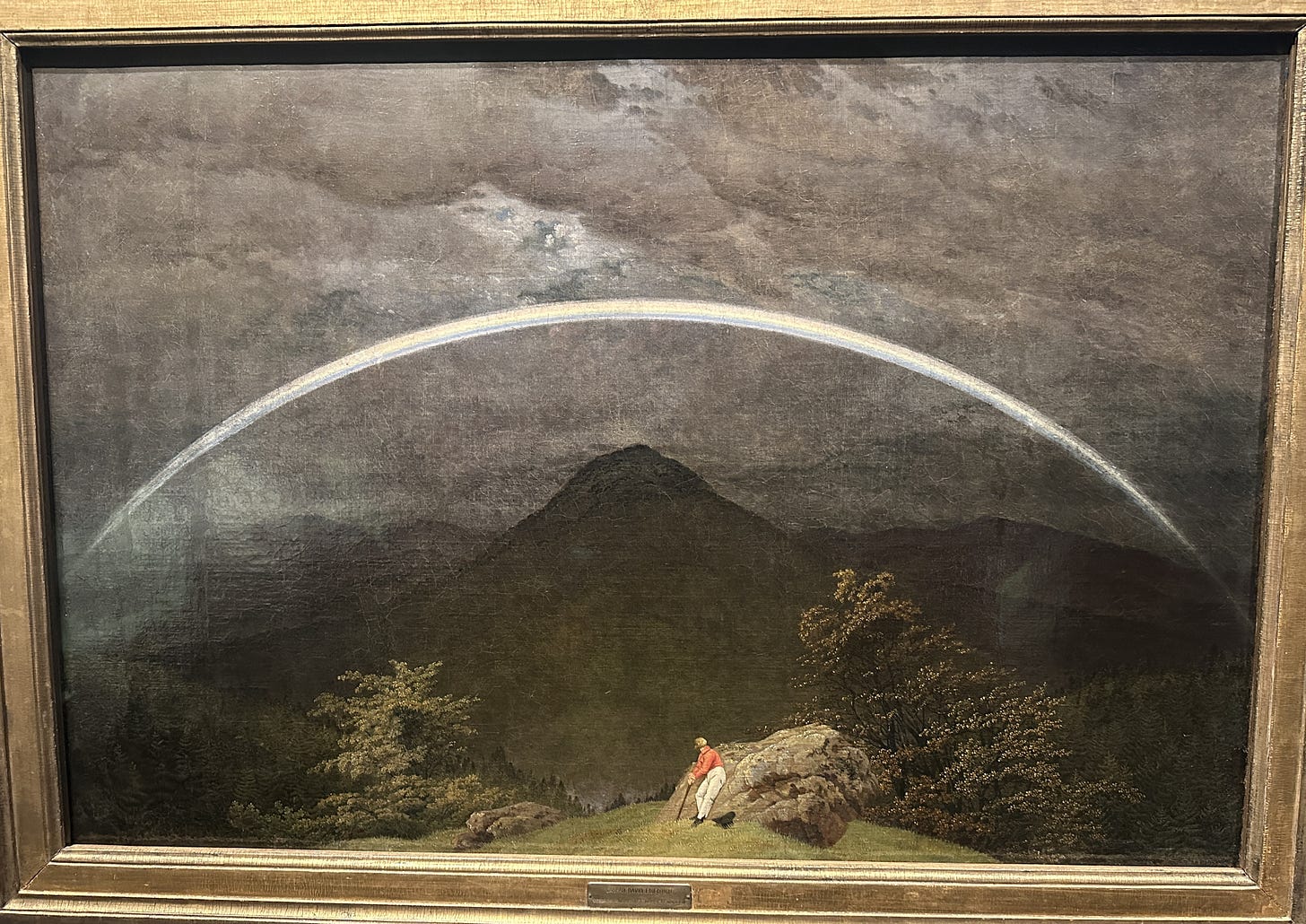

(Mountain Landscape with Rainbow, Caspar David Friedrich, 1810)

“Mountain Landscape with Rainbow” is one of Friedrich’s earlier works. It contains many familiar elements that we all know and love, such as the beautiful mountains, the lone wanderer with the infamous cane, and a striking depiction of the weather conditions. It’s a very large painting, a fact that is underappreciated if one only sees this painting online. The curators intelligently placed this painting next to a much more famous one.

(The Monk by the Sea, Caspar David Friedrich, 1810)

“The Monk by the Sea” is a painting that I’ve written extensively about. Indeed, this is one of my absolute favourite paintings, and it was such a joy to witness it in person finally. Seeing it right across from “Mountain Landscape with Rainbow” really deepens the point that Friedrich was making with these two paintings. Also, the fact that they were both made around the same time makes us understand that this theme of “Man vs. Nature” was of particular interest to Friedrich.

The similar composition, both portraying a small man overpowered by a massive landscape portrayed in two different settings, drives the point home even deeper.

(Winter Landscape, Caspar David Friedrich, 1811)

One painting that I was particularly thrilled to see in person was “Winter Landscape,” which has always been one of my favourites.

A young man stands alone in a snow-covered landscape, holding a walking cane. A few barren trees surround the man, but nothing else can be found in the distance. The Rückenfigur technique Friedrich employs leaves the man's emotions ambiguous; we cannot easily discern if he's fraught with fear or driven by curiosity. This ambiguity enriches the painting's mystique, inviting us to ponder if he faces peril or is in pursuit of something.

The two large trees at the forefront could potentially abstract our view of what the man is looking at. Those trees create an interesting visual element; they divide the painting into two, and the fact that they continue outside the frame makes the viewer realise that there’s more than meets the eye. There’s definitely more happening in this scene; we can’t tell what it is. The man, who is situated right between those two trees, resurfaces the same theme of “Man vs. Nature” we’ve seen in the previous scenes.

Let me ask you: Who is the hero in this scene? Is it the man or the trees? Which seems more important? I don’t know the answer to that, but it’s an interesting question to think about. This thematical ambivalence so common in Friedrich’s art is what makes it so intriguing for me. It leaves room for speculation. We can make many different stories about that man; maybe he’s a hunter looking for deer or a lost wanderer looking for an escape from the frozen wilderness. It’s up to us to decide.

(The Chasseur in the Forest, Caspar David Friedrich, 1814)

Continuing with the theme of a lone wanderer in the snowy landscape, we encounter “The Chasseur in the Forest.”. This picture depicts a cavalryman, a soldier, facing a thick, menacing forest alone. One thing viewers immediately commented on when I heard them talking to each other near the painting was the fact that there was no horse. A chasseur alone in a forest without his horse—something must’ve gone wrong. Indeed, Friedrich is far less ambivalent with this painting than the previous one.

We can also see the two tree trunks in the front, with a black crow standing on top of one of them. The crow is a symbol of great misfortune, even death. This young man had to come from the battlefield, and now he’s alone, facing the elements. Perhaps the enemy awaits him in the forest for one final blow. The soldier certainly isn’t looking weak. He is standing with a straight posture, looking ahead to what’s in front of him. But his chances definitely seem slim.

(The Sea of Ice, Caspar David Friedrich, 1824)

Moving on to another classic, I encountered “The Sea of Ice” for the second time in my life. What a joy it is to behold this monumental picture. It’s one of Friedrich’s largest paintings, and it’s striking, dramatic, and beautiful. I dedicated an entire post to this painting, and I highly recommend reading it here.

The new takeaway from this encounter was the special way this art was conceived. Friedrich (unlike Peder Balke) never ventured into the Arctic North. Indeed, he had never seen ice formations in his entire life, except for one instance:

“The winter of 1820/21 in Dresden was exceptionally harsh, with the result that the river Elbe froze over completely for a time. Friedrich was among those who found the subsequent ice drift—a rarely observed naturally occurring phenomenon—deeply fascinating. He usually sketched outdoors with just a pencil and sketchbook, adding colour to his compositions only when he had returned to his studio, far from what he had seen. On this occasion, however, he took all the necessary painting materials with him when he visited the banks of the river. In his detailed sketch, Friedrich focuses not only on the angular shapes but also on the different colour values of the frozen blocks of water.” [1]

So Friedrich reverse-engineered his imaginary “Sea of Ice” scene, using some ice floes he found by the river. He combined his lessons on ice with the stories he heard of expeditions to the North Pole, resulting in the striking image of the “Sea of Ice.”

To us, people living in the age of information, the thought of not knowing what ice looks like is bewildering. This makes me see this painting not only as a beautiful seascape that speaks about man’s transience being on earth against the sublime power of nature, but also from a historical perspective, as a prime example of the work of an innovative artist. An artist who kept pushing towards reaching new, unknown landscapes. This second encounter enabled me to unlock a new dimension from which to see this painting.

Now, finally, to the “icing” on the top:

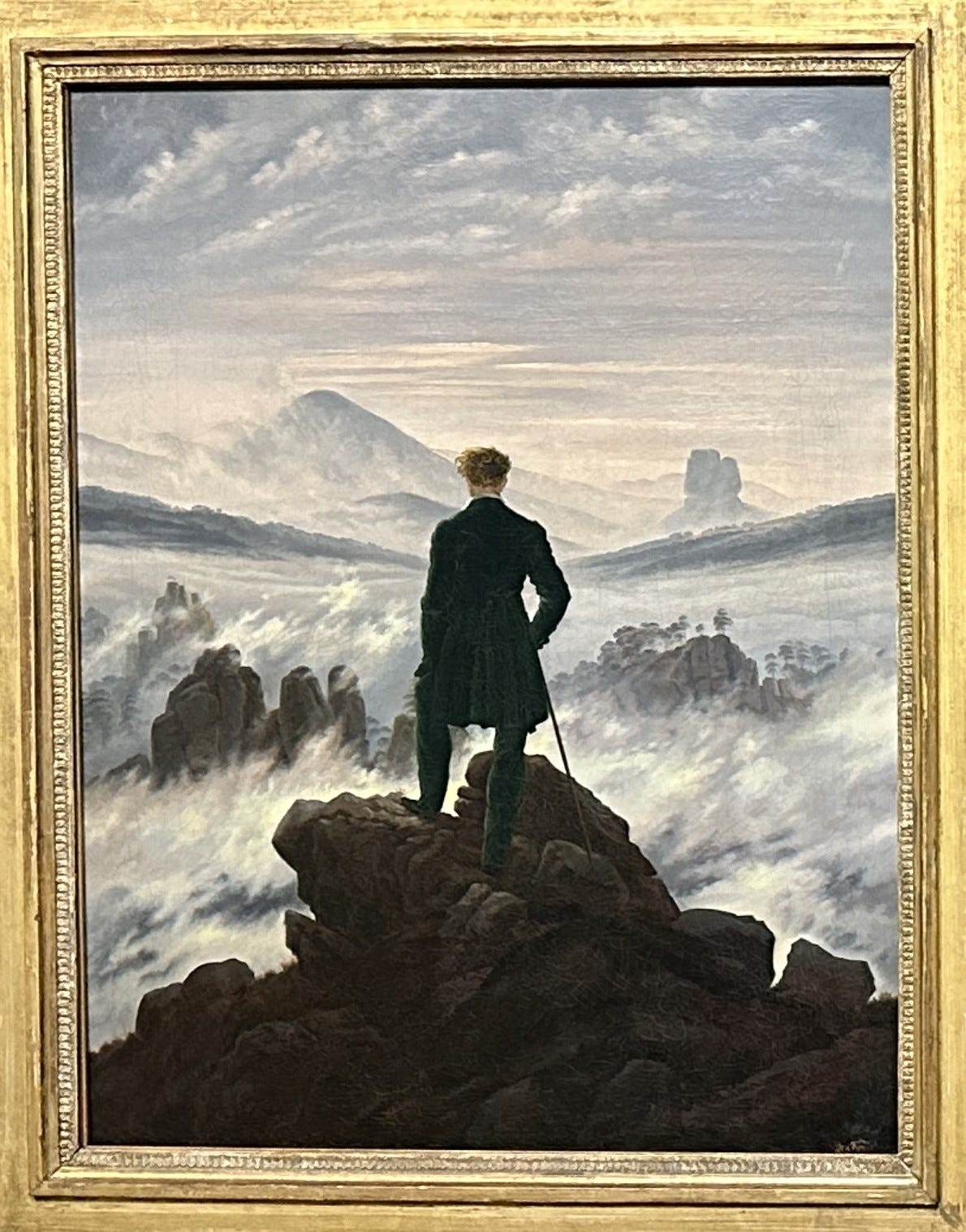

(The Wanderer Above The Sea of Fog, Caspar David Friedrich, 1818)

Obviously, the most crowded room was the one with “The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog.” It was very difficult to have a more intimate moment with the painting, as I usually do. Still, nevertheless, I managed to have my few candid moments with “The Wanderer,” which made me very happy. I have written about this painting many times, so I won’t reiterate my points about it.

The thing I enjoyed very much this time was witnessing how much so many people appreciated it. Even when I walked around the city of Hamburg, I could see numerous posters of the painting all over. This is an icon, and I love that fact. Generally speaking, the fact that the exhibition was totally sold out and packed with people from all over the world to see the great art of Caspar David Friedrich speaks volumes. There’s something about this art that touches the masses’ hearts. People see themselves in the place of the Wanderer; they aspire to be like him.

Until next time, Herr Wanderer.

Concluding Thoughts

(Two Men Contemplating the Moon, Caspar David Friedrich, 1820)

There were many more awesome works that I have yet to cover, including many works by other interesting contemporaries of Friedrich. I will save these for future posts. Now, to conclude with some general observations:

An unfortunate thing regarding that exhibition, which is titled “Art for a New Age,” is the (unsurprising and unoriginal) connection the curators make between the environmentalist movement and Friedrich. It’s even apparent in the description texts they wrote for his original works, not only for modern ones, which was quite sickening to witness. How dare they assume that Friedrich would endorse that? But if the fact that people somehow think that Friedrich’s art is endorsing environmentalism leads to more people being exposed to it, it would be a very positive outcome. So, a good thing might come out of it, but this connection to the green movement is entirely inappropriate.

Another negative aspect of the exhibition that should be noted is that it included two other parts dedicated to contemporary references to Friedrich's art. In principle, I don’t object to it; I think it’s ok to include contemporary paintings that pay homage to Friedrich, but I’m starkly against paintings from the likes of Kehinde Wiley, who simply copies Friedrich’s masterpieces and places figures of colour instead of the ones in Friedrich’s works. I find that deplorable, and it should be condemned. That being said, a few pretty works of photography were included in the exhibition, which I actually enjoyed. It struck me more as a homage rather than a mockery (which is what Willey is doing).

One of the things I’ve noticed about this exhibition is how much I could dive into that sense of calm, tranquil unity with nature. Virtually all the paintings in the exhibition display the same gentle whistle sound of wind; I could feel these cold German forests and mountains as if I were there with the Wanderer. I could hear the birds chirping; I could feel that sense of intrigue that arrived from witnessing a piece of natural beauty by these many “Wanderer” characters. You don’t get that when you see one or two Friedrich works in a museum filled with many other works. I was able to immerse myself in a special aesthetic experience. Integrating many works by one painter elevated my perspective and enhanced my ability to connect with the world of Friedrich in the most profound manner possible in recent history.

The combination of all these Friedrich masterpieces is in itself sublime.

Friedrich's art takes one on a journey into a world unknown to us in our modern age. The emergence of the smartphone makes it very difficult to become one with nature, like the heroes of Friedrich's works.

This is not only because phones distract us but also because they add another “objective” to a natural hike, which did not exist before—to take pretty pictures.

Whenever I see a beautiful landscape, I first have the urge to take a picture before I actually manage to enjoy it. If there’s one lesson from Friedrich that we can immediately apply to our lives, it is to contemplate. Take a deep breath and enjoy the wind, the achievement, and the beauty surrounding you. Go out to nature, seek natural beauty, and really soak yourself in it. It’s not easy, but it’s so worth it.

Think about “The Wanderer”: How much time do you think he spent on that summit? It wasn’t a mere 2 minutes.

I’m so glad I could attend this momentous occasion in Hamburg. I will cherish these memories for many years to come. An enormous thank you to all those who had to do with making this exhibition a reality.

Thank you for reading Philosophy: I Need It. If you enjoyed it and want to see more content, consider supporting me by clicking the button below. Every dollar counts.

[1] Text from the exhibition’s textbook