Mahler’s Fifth Symphony Explained

A Philosophical Hero’s Journey in Music

Prologue

The man who strives,

despite whatever happens along the road,

the one who keeps on going,

shall live in eternity.

This is a story about the human struggle.

The strive to reach the ultimate summit,

Eternity.

The costs of that strive,

and the incredible reward.

This is my attempt at expressing the inexpressible.

That which only music can truly express.

For this music, it is the ultimate work of art and philosophy.

You have to experience it.

You owe it to yourself.

Satz I. Trauermarsch Metaphysics

A solo trumpet makes a declaration.

I remember the first time I heard it—live, in Cologne. The very first second the trumpet sounded, my face broke into a smile. I knew at once: this was going to be an extraordinary journey—a journey unlike any other.

At first, it recalls Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, the most famous opening in classical music. But there is a crucial difference. Beethoven begins with an orchestra—a whole people, a collective force announcing itself. Mahler begins with a single trumpet. One man. One voice. This is not the voice of a nation or of fate itself. It is the voice of the individual. That matters. Remember that “one”—it will return later.

And then, almost immediately, we plunge into the Trauermarsch, the funeral march. The world grows dark. This symphony begins not with noble mourning but with grief laid bare—private, stripped of protection, raw. Mahler begins where most composers would be afraid to linger: in unguarded sorrow, without the armour of heroic purpose.

And here is something I believe without hesitation: if you—or anyone you know—refuse to listen to classical music, then take just the first twenty or thirty seconds of this symphony. The solitary trumpet, the plunge into the powerful funeral march. If that doesn’t intrigue you to hear what comes next, then give up. It’s no use. Nothing else will.

That trumpet does not vanish; it threads through the movement with relentless persistence. Around it, the orchestra gathers in layers of mounting grief. Woodwinds speak in broken gasps—oboes and clarinets choking on their own sorrow, flutes fluttering like last breaths. But gradually the brass takes command. Horns, trombones, tubas swell until they overwhelm everything else, drowning out fragile woodwind voices in waves of metallic power. The strings struggle beneath this assault, while the timpani pounds the sorrowful tread with pitiless force. This is not gentle mourning—it is brutal, forcing us to confront death without mercy or consolation.

And then, at the end, the trumpet returns. The same solitary call that opened the movement now fades into silence. The individual voice, once defiant, now diminished. Not resolved, not redeemed—only silenced.

And if you have come to classical music through the Russians—Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff—as I did, this opening might surprise you. There are no lush, beautiful melodies here, no romantic swooning to sweep you away. It’s not a flaw, it’s a feature.

Mahler is not offering beauty up front. He is establishing the framework: Where are we? What are we up against? What point have we reached in our lives? What lies ahead? The first movement is a metaphysical statement, designed to locate you spiritually and psychologically; to reach beauty, we must earn it.

And that is the crucial truth the greatest composers understood—Beethoven above all. A resolution means more when it has been earned. A conclusion is most profound if it lifts one from the depths. That is why Mahler begins here, not with grandeur but with undefended grief—because only in confronting death without any sugarcoating can triumph become not just believable but true.

Satz II. The Storm

If the first movement is the solemn declaration of death, the second is the storm that follows—the turmoil after the trumpet has told us that which we did not want to hear. This is grief processed, but not calmly. It is grief erupting and spiralling upwards and downwards, a grief that shatters any sense of quiet composure.

The connection between the two movements is immediate and intimate. The trumpet calls from the previous movement echo through the storm of the second, transformed and twisted, as if the very themes of the first movement are being hurled about in chaos. These are not new materials but the same cries, broken apart and reassembled in violence.

Here is where the contrast with Beethoven is clearest. Beethoven, in his own storms, wrestles with fate as an equal—hero against hero, a duel of strength. Mahler does not wrestle. He lets fate tear him apart, understanding that through destruction, a more profound reconstruction is possible. This is not a noble struggle. It is a total collapse. And that collapse will serve as the foundation from which the symphony will rebuild itself.

One of the most striking elements is the dialogue between strings and woodwinds on the one hand and the brass on the other. The strings and woodwinds attempt lyrical passages—fragile, searching lines, almost like the human voice trying to sing its way through suffering. But these attempts are constantly overwhelmed by the brass, blunt and merciless, the sound of fate itself. What unfolds is not a resolution but a spiralling grapple: the human spirit reaching upward, only to be hurled back down by forces larger than itself.

Out of the chaos, a fragile optimism begins to rise. It starts in the cello—the instrument closest to the human voice—and spreads through the strings and woodwinds. This is the human element asserting itself. The brass retreat into the background while the strings climb upward, building passages of great beauty and warmth. For a moment, there is harmony, even synthesis, as if the entire orchestra were singing one common song.

But at the very peak, the trumpets intrude, cutting through the lyricism, overpowering the rest. The vision collapses. What follows is a struggle—back and forth between brass and percussion on one side, strings and woodwinds on the other. Brief glimpses of melody and beauty appear, but they never last. Nothing is given easily; everything is hard-won.

Eventually, the orchestra gathers itself into an epic declaration. The material of the Trauermarsch returns, but not as a solitary trumpet—it is now the full orchestra, united, resilient, stronger, infused with power. Yet even this is not a triumph. The movement does not end in victory but in ambiguity. The storm subsides into a mournful quiet, the shadow of the funeral march still present.

This is why Mahler marks it Stürmisch bewegt—stormy. That is the essence. It is not resolution but struggle. If the first movement was the recognition of death, this is the battle that follows: the human spirit against fate, beauty against destruction. And it is absolutely glorious.

Satz III. Dancing with Fate

And then we reach the middle movement—the Scherzo, the largest of them all. Most performances run close to twenty minutes, sometimes more. It is a vast cathedral of sound, a sprawling dance that towers over the entire symphony.

Here the character changes completely. After the grief of the Trauermarsch and the fury of the storm, we enter a new world. The brass, once violent and overpowering, are now more subdued. The soundscape is transformed. What had been brutal now feels grotesque, playful, even mocking. It is still unsettled, but it dances.

This is the first breakthrough—the reassertion of life. Not noble, not orderly, but chaotic, strange, unmistakably alive.

Here, against the second movement’s violent grappling—sections of the orchestra colliding like enemies—we now hear something different. The instability is still there, but it has changed character. The orchestra, though restless, seems to have made a kind of uneasy truce with itself.

It is as if the brass, the winds, the strings have all realised: none of them can truly dominate the others. They are stuck together in this orchestra, bound to one another whether they like it or not. And so they might as well dance. That is perhaps what much of life really is—not the end of conflict, but its transformation into rhythm, into motion, into something survivable.

This strange, unstable dance is led above all by the horns. They rise again and again, calling out with a swaggering confidence. Sometimes it feels rustic, like a village band; sometimes it feels noble, like a proclamation from the hills. But it is always insistent, as if reminding us that life, once it has found a voice, refuses to be silenced.

In the first half of the Scherzo, we reach a decisive moment: the horns break out in a grandiose solo that forces us to take stock of where we are. It recalls the solitary trumpet that began the symphony and closed the storm of the second movement. But this time it is different. The trumpet was stark, even merciless. The horns are warmer, more humanistic, and even noble. The cellos answering the horns underline this change—no longer death’s proclamation, but a dialogue with life.

Another horn cry follows, and then comes the surprise: the strings slip in with gentle plucking, while the rest of the orchestra falls nearly silent. It is playful, ironic, perhaps even humorous. After so much grief and struggle, here is a breath—a lightness we had not thought possible.

From here the music takes on the intimacy of chamber music, a small group spinning delicate, melodic phrases while the trumpets fade into the background. It feels like a reprieve, a moment of genuine breathing space. For the first time since the funeral march, we sense that perhaps victory is possible. Perhaps the journey can end in triumph after all.

This is the genius of the Scherzo: it not only lives in the concert hall. It can step into the street, uninvited, and claim you. It found me once, in Boston.

Mahler in the Streets of Boston

As I walked through the old city streets,

I turned right into a kind of alley.

But something made me turn back.

I continued a little further on the main road.Suddenly I stopped.

I heard something familiar.

I drew closer.

I froze.It was this.

I had no doubtIt was the third movement,

the Scherzo — from Mahler’s Fifth.What are you doing here?

— Boston, July 4th, 2025

That is Mahler’s Scherzo: uncanny, grotesque, alive—appearing where life itself pulses most strongly.

As the music develops and we enter the second half of the Scherzo, we encounter something new: a lush, melodic passage that opens the heart. It is as if the music is preparing us mentally for the possibility of love. Not love itself—that is to come later—but the possibility.

But not so fast.

Almost immediately, we are thrown back into the dance, more grotesque than ever. You think you can reach the promised land so easily? Not so quickly. Life doesn’t give it to you like that. The storm returns, but now with more interplay, more back-and-forth. The unusual clapping sounds punctuate the struggle, hammering back and forth until finally the horns enter again, restoring a sense of order—if only for a moment.

The dance resumes, faster and more intense, until it seems it could spin on forever. Then suddenly the horns erupt in another grand solo, halting the orchestra in its tracks. Once again, they remind us where we are and how far we have come since the solitary trumpet of the first movement. Alone, the horns hold the stage, commanding silence around them.

What follows is another gentle passage, echoing the earlier chamber-like interlude with its plucking strings. This time, however, the music leads into a heart-opening string passage like the one before—but now it is carried forward by the horns themselves. It is as if the symphony is drawing closer to being fully open, preparing us to receive music’s greatest gift, which is about to come very soon.

And yet, before the end, Mahler demands one last eruption: the brass and percussion unleash another furious climax, a final grotesque whirl of the dance. Only after this last frenzy does the Scherzo conclude—reminding us once again that nothing in life comes easily, not even joy.

Satz IV. Life’s Greatest Gift

Before I even put on the Adagietto and listen to it for the millionth time as I am writing this essay, I think to myself: how dare I say a word about that which explains itself in the clearest, most lucid way one could possibly imagine?

So before anything, take ten minutes of your time and listen to the greatest gift Mahler has to offer us—perhaps one of life’s greatest gifts. If you have not discovered this yet, I hope you will revere this moment, because there is nothing quite like the first time you listen to the Adagietto.

After all we have been through—the great cry of the trumpets in the first movement, the storm that followed in the second, the grotesque yet powerful dance of the Scherzo—we arrive here. The Adagietto.

It opens with strings and a harp. A gentle, candid, vulnerable sound. An open heart. No percussion layered over it, no brass, not even woodwinds. Just the strings—and above them, that divine harp.

Yes, there were hints of this in the Scherzo, if we remember, little passages that gave us a glimpse. But this is different. This is nothing like what we have experienced so far. It is a stark departure. It is simply a song. A song of a man’s feelings. Perhaps the most beautiful song ever written.

And even here, there is struggle—but it is the most personal kind. Directly from the composer’s heart. When you reach the peak of this music, and the harp strikes at the very summit, your heart melts. You realise how foolish you have been to go through life without allowing yourself this gift, without realising that such naked vulnerability was possible—and how much can come of it.

It is the ultimate proof. There are very few other musical pages that can achieve this degree of emotional openness, and the majority of them are also Mahler's. Proof that we need the struggle, we need the storm, and we need the darkness to make ourselves worthy of the gift. For if we do not strive, we never reach the summit. The harp will never sound for us.

And this is also what sets the Adagietto apart from other sublime short pieces of music. Take Rachmaninoff’s Eighteenth Variation, for example. It is magnificent, and you can listen to it on an endless loop—it gives itself immediately, without resistance. The Adagietto is different. It is not an isolated jewel but the product of an entire journey. Even on its own, it is almost unbearably heavy, too intense to return to often. Its beauty is inseparable from the vulnerability it demands.

That is Mahler’s gift: he never flatters you cheaply. His music makes you work, and only then does it reveal its summit.

And what is life for, if not that?

Satz V. The Ultimate Celebration

After the gift of the Adagietto—love stripped of borders, offered in its purest form—we breathe. We may shed a tear, or we may not. But now we know. We know that something is coming.

And then it bursts forth: the Finale.

The first part of the Finale is a constant layering upward. Strings lead, interjected by brass, each phrase pushing higher, always building. There is an unmistakable sense of continuity, of upward momentum.

The contrast with what has come before could not be sharper. Compared to the sombre cry of the first movement, the storm of the second, even the grotesque dance of the Scherzo, this feels different—almost classical. At times, it sounds as though Mahler is deliberately evoking a more traditional finale structure, even a Beethovenian one, with its linear build-up and its drive toward resolution.

And yet, it is never merely traditional. Mahler takes that familiar shape and floods it with his own voice: exuberant, overflowing, completely unguarded.

The Finale builds and builds until it feels as though we have reached the end—only for Mahler, in his unmistakable way, to pull back. The music lingers, slows, lets us breathe. Yet beneath it all ,the rhythm keeps pressing forward. You feel it: something is about to erupt.

But unlike the sudden hammer blows of the Sixth Symphony, this is not shock. This is an expectation. After the emotional roller coaster of the first four movements, Mahler seems to say, ‘Now, at last, relax. Celebrate.’ Enjoy these final minutes with me. The joy of life, the joy of love attained in the Adagietto—here it bursts forth, eruptive, orgasmic, unrestrained.

By now there is no longer any animosity between trumpets and strings, no conflict between sections. We are at peace. The orchestra plays in harmony, each group bursting with joy, tossing it back and forth in radiant celebration.

And yet Mahler still reminds us—especially in those sudden slowings before the end—that victory never comes easily. Life is not like that. To truly celebrate, one must first endure. One must earn it. Only then does the triumph ring true. Mahler presses this point until the very last moments of the symphony.

And right before the end, the music toys with us. The woodwinds slow down into a playful, lyrical moment, as if to suggest: perhaps this will not end as symphonies usually do. Perhaps the Beethovenian conclusion we long for will be withheld.

And then—it arrives. An eruptive explosion, the entire orchestra in full cry, celebrating life. The Fifth ends as the ultimate celebration, but not a shallow one. It celebrates in the most honest, emotionally vulnerable way possible—because it has faced the tragic and the sad. How can we celebrate if we have not reckoned with grief? That is what Mahler teaches us.

The fifth is the ultimate lesson: we want the happy ending so badly, but we must first be made worthy of it. And Gustav makes us worthy.

That is why there is nothing more festive, nothing more honest, nothing more human than Mahler’s Fifth Symphony.

At the Concert, at the Conference

I’m sitting here at the American conference.

For the Fourth of July, they arranged a festive concert with a small orchestra.

They’re playing American marches, waltzes—even operettas.

Is this a true celebration?No.

For me,

there is no music more festive than your Fifth.

You—who know how to appear anywhere,

even on this day,

in this unrelated city,

on this unrelated street.Where I come from,

independence comes after memory.

Not just to celebrate—

but to hear the trumpet of the Trauermarsch,

the storm that follows,

the colossal Scherzo,

the Adagietto’s summit of beauty,

and the epic finale.That is the ultimate celebration music.

It speaks the truth.

It cuts the deepest.That, and no other.

Happy Independence Day.

Boston, 4/7/25

Epilogue

Goethe’s Faust journey famously ends with:

"Wer immer strebend sich bemüht,

Den können wir erlösen."

(“He who strives on and lives to strive

can earn redemption still.”)

It’s a profound idea that has lingered in my mind for a long time. After listening again to Mahler’s 5th, particularly for the first two movements, I see this same idea:

Life is about that endless striving.

Just as Mahler had continued to compose and conduct until the very end of his life.

Just as he had continued to work on his symphonies after publishing them, despite all that was going on in his tremulous life,

He marches on.

And that endless striving is what made him reach the eternal.

His fifth symphony is the ultimate instrumental manifestation of this divine idea.

If you still don’t see how,

It’s ok.

It took me a long time to understand that.

As Mahler concluded his final choral work, Das Lied von der Erde:

“The dear earth everywhere

blossoms in spring and grows green anew!

Everywhere and forever blue is the horizon!

Forever ... Forever …”

Thank you for reading Philosophy: I Need It!

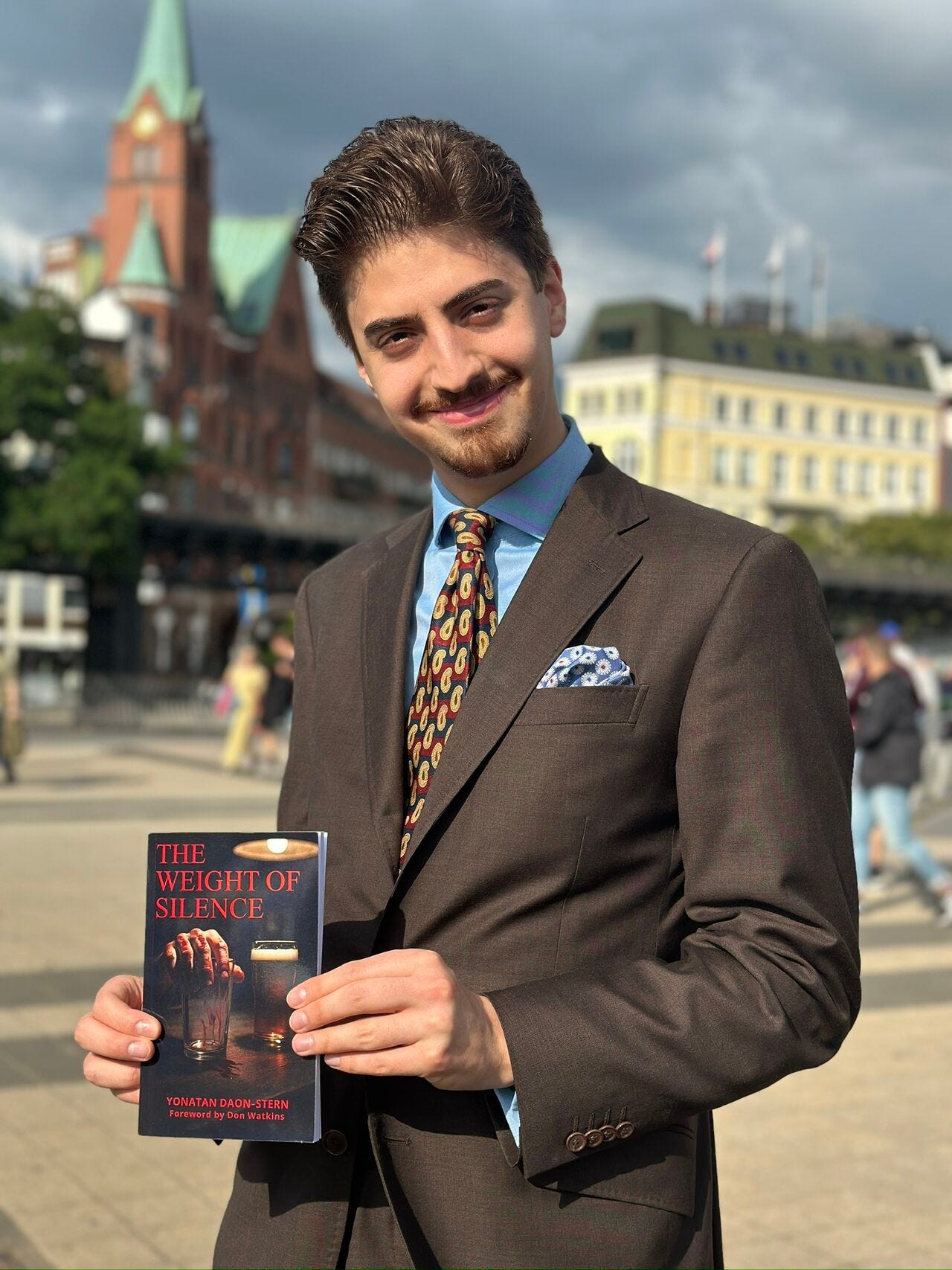

I’ve just released my debut novella, The Weight of Silence. You can buy it on Amazon.

If you want to support Philosophy I Need It—fiction, essays, and everything in between—consider becoming a monthly member or making a one-time contribution here. Every bit helps me create more and better.