Don’t Be Scared of Mahler!

A Listener’s Journey into the Epic Symphonies You Think Aren’t for You

I. Introduction – My Journey Begins at 40,000 Feet

I was told by my musically affluent friends not to do this—but I ignored them, and I’m so glad I did.

One habit I developed on long flights was listening to slow, expansive symphonies. My first encounter was with Schubert’s Ninth—“The Great.” It’s a curious piece: full of repetition, yet always moving forward. Much like a flight, it covers a vast distance without feeling rushed. It’s soothing but not dull, gentle yet dramatic. Over the years, it became my ideal travel companion—and, unknowingly, my gateway into the so-called epic German symphonies.

It takes time for The Great to unfold. It took me some time to learn how to enjoy it. But through repeated, almost passive listening, I grew attuned to its rhythm. Now, I don’t just fall asleep to it on aeroplanes—I sit with it in full attention, the way one might listen to a Rachmaninoff piano concerto. It was my first taste of the long-form symphony—and I didn’t need a degree or a guide. Just time, curiosity, and a pair of headphones.

🎧 Recommended recording: Josef Krips, with the London Symphony Orchestra.

II. The Myth of Difficulty

Mahler’s name is often surrounded by a sense of dread. “Too long, too dense, too complicated.” Even among musical friends who admire him, the advice is cautious: ease into it. Start with Mozart. Then maybe Beethoven. Maybe the Russian Romantics—Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninoff—because their music grabs you immediately. It’s emotional, it’s accessible, and it doesn’t ask for too much patience.

But here’s the truth: Mahler can grab you just as fast.

Start with the first movement of his Fifth Symphony. Those epic trumpet calls? They hit like fate itself. It doesn’t take analysis or preparation—it just demands attention. And it gets it.

The supposed "difficulty" of these epic symphonies doesn’t come from their content. It comes from us—from the way we live now. We inhabit the shortest attention span in human history. We scroll, swipe, and skim. And in that context, anything that unfolds slowly, over time, feels “hard”—even when it’s deeply human and rewarding.

Symphonies like Mahler’s or Bruckner’s aren’t hard because they’re abstract. They’re “hard” because they require what modern life rarely does: stillness, patience, and long-form listening. But once you give yourself to that scale, you realise: they’re not walls to climb—they’re worlds to enter.

🎧 Recommended: Mahler’s Symphony No. 5, Movement I (Start here, then go further.) – Leonard Bernstein, Vienna Philharmonic

III. The Revelation of Live Music

My first real breakthrough with Mahler—like many of my musical awakenings—came courtesy of the Israel Philharmonic in Tel Aviv. They performed Mahler’s Fourth Symphony, and it was out of this world. The slow third movement in particular—it’s so tender, so quietly radiant. That’s when it hit me: even a musical mortal like myself could enjoy Mahler. It opened up a whole new world of possibilities.

But the truly life-changing moment came later, in the German city of Cologne.

There, I had the honour of hearing a live performance of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony.

Until that evening, I had never listened to the Fifth in full. I knew of it, of course—especially the famous Adagietto. But I had never experienced the entire arc. I had never been pulled into the full, integrated sweep of its five movements.

And what an experience it was.

One of the greatest gifts that night gave me was simple: I had no choice but to sit, listen, and be soaked into Mahler’s world. There was no pause button, no distraction, no way to break the spell. And that forced immersion—total, involuntary immersion—was invaluable. It showed me that sometimes, the only way to truly experience something as great as a Mahler symphony is to surrender to it completely.

Especially the ending. My God… the ending. It’s not just triumphant—it’s a burst of joy, a flood of energy, an orgasmic explosion of life. It doesn't just lift you—it launches you. It was something completely outside of the ordinary. Something sublime.

That night changed how I listened to music and how I understood art itself. Sitting there, I felt Mahler’s presence—not as a figure of history, but as a living mind reaching across time to speak to mine. His struggles, his triumphs, his longing—they were all there, immediate, personal. And it taught me: great art isn’t a performance. It’s a meeting of souls.

And ever since then, every time I listen to the Fifth, I feel energised. Not just moved—charged. It’s much better than a double espresso, believe me. It’s like the music rewires you from the inside and sends you back into the world with more life than you walked in with.

🎧 Recommended: Mahler’s Symphony No. 4, III Movement – Barbara Hannigan with London Symphony Orchestra

IV. You Don’t Have to Work Your Way Up

I began with Schubert at 40,000 feet, slowly learning to love long-form music the way one learns to enjoy stillness. But with Mahler—especially the Fifth—I discovered that these so-called “difficult” symphonies aren’t just calm and grand—they can be more energising than a literal caffeine hit, every single time.

And that’s when I realised something else: you don’t have to work your way up to this. You can just dive in.

Yes, I first fell in love with classical music through Rachmaninoff’s Second Piano Concerto—a piece that grabs you by the collar from the first note and doesn’t let go until its glorious ending. But honestly? That could just as easily have happened with Mahler’s Fifth, had I sat down and listened to it in the same way.

So that’s what I urge you to do: try. Don’t treat these symphonies like some academic Everest you need to train for. Just sit down and see if the music touches you. Give it a proper chance, a real listen.

You might be surprised how quickly it speaks.

🎧 Recommended: Mahler’s Symphony No. 5 – Claudio Abbado with Lucerne Festival Orchestra

V. The Unmatched Reward

By now, you might be thinking: Alright, I get it. You like Mahler’s Fifth. And yes—I do. But what I’ve found is that the reward of these epic symphonies isn’t limited to one piece. It’s something structural, almost philosophical.

There’s a kind of joy that only comes from following an idea, a mood, a struggle—unfolding patiently over 45, 60, 80 minutes. This isn’t the immediate hit of a pop hook or a romantic melody. This is narrative at the scale of life. Tension builds. Themes return changed. Resolution feels earned. And when that final movement explodes or glows into silence, you’re not just a listener. You’re a participant.

That’s what allowed me to attend and deeply enjoy a live performance of Bruckner’s Fourth Symphony—a concert I would have avoided just a year earlier. Before, I would’ve thought: “That’s way too long. I’ll never make it through.” But because I had already experienced that slow, immersive world in Schubert and Mahler, I was able to enter it. And it was magnificent.

Likewise with Mahler’s First Symphony—a piece I listened to one afternoon, and by the end, I was smiling like a fool. The final movement lifted me like a wave. And I knew: this is no longer difficult music for me. This is my music now.

This is what these symphonies give you: transformation. A kind of narrative and emotional arc that you live through. It’s not just art—it’s a form of metaphysical renewal. And in a world that pulls your attention in every direction, you owe it to yourself to experience something this deep, this beautiful, this human.

VI. Why The Scale Matters

These symphonies aren’t just long. They’re not just dramatic. They’re epic—and that scale isn’t accidental or indulgent. It’s central to what makes them so powerful. Their size, whether in duration, orchestration, or emotional range, is the very thing that allows them to say something greater than almost any other art form can.

We live in an age of the short. Short songs. Short thoughts. Short bursts of emotion. But Mahler and Bruckner weren’t writing for distraction. They were building cathedrals of sound, meant to be entered, explored, and lived through. Their symphonies take time because the truths they deal with—life, death, grief, transcendence, purpose—take time. You cannot compress the experience of being alive into three minutes.

With Mahler, the scale is often literal:

In his Second Symphony (“Resurrection”), he writes for full orchestra, multiple soloists, and a vast choir—not as ornamentation, but as the necessary medium for a work that dares to speak about death and the triumph of the soul.

In the Eighth Symphony, he brings in massive choral forces to give voice to mankind's greatest yearnings—love, redemption, transcendence.

Even in his purely instrumental symphonies, like the Fifth, the range is staggering—from the whispered intimacy of the Adagietto to the eruptive horn calls of the finale. Mahler didn’t compose to please—he composed to elevate.

With Bruckner, the orchestras were not unusually large—but the spiritual ambition was towering. His symphonies are not soundtracks for life—they are statements about man’s place in the universe. Listening to them is like entering a sacred space built by one man’s devotion to the sublime. The slow unfolding, the monumental arcs, the feeling of timelessness—they are all deliberate. He wanted you to feel not lost, but oriented toward something greater.

Even Schubert’s Ninth, which first captured my imagination during long-haul flights, is a symphony of scope. It doesn’t rush. It builds slowly, breathes deeply. It rewards patience. And by the end, you’re not just impressed—you feel like you've traveled with it, and emerged more whole.

This kind of scale isn’t about spectacle. It’s about ambition. These works attempt to give form to the grandest ideas of the human spirit—and to lift the listener to their level.

And that scale turns these symphonies into events—not in the casual sense, but in the deepest one.

Think of Mahler’s Second Symphony. When the final movement begins and the choir rises, it doesn’t feel like a performance—it feels like a revelation. A moment of spiritual exaltation that belongs among the great achievements of Western art. Or think of Beethoven’s Ninth, where the idea of freedom itself becomes music. These works don’t just impress—they demand that you rise to them.

They don’t dissolve you into a collective. They awaken the individual, remind you of your capacity for greatness, and affirm the best within you.

This is what scale makes possible: not a communal ritual, but a personal triumph.

A triumph of listening. Of attention. Of staying long enough to be changed.

These works are celebrations of civilisation itself—of reason, order, beauty, grandeur, and human meaning. They are monuments to what it means to live consciously, to pursue the sublime, to deserve joy.

In a world constantly urging you to shrink your focus, to rush, to forget—these symphonies stand as defiant affirmations of what is highest.

And once you experience that—once you give them the time to carry you there—you’ll understand: The scale is not a challenge. It is the reward.

VII. This Was Never Elitist Music

One of the most persistent myths about long symphonic music—especially Mahler or Bruckner—is that it’s somehow elitist, or “not for ordinary people.” It requires a formal education or a music theory background to be appreciated.

This idea is not only false—it’s a historical distortion.

We must understand that this music was not composed for a select group of experts, but for the masses of Carnegie Hall. Or the Viennese public. Or the concertgoers in Hamburg, Vienna, Prague, and beyond. These were composers who wanted to move people, not intimidate them.

In fact, many of them faced resistance from the elite of their time.

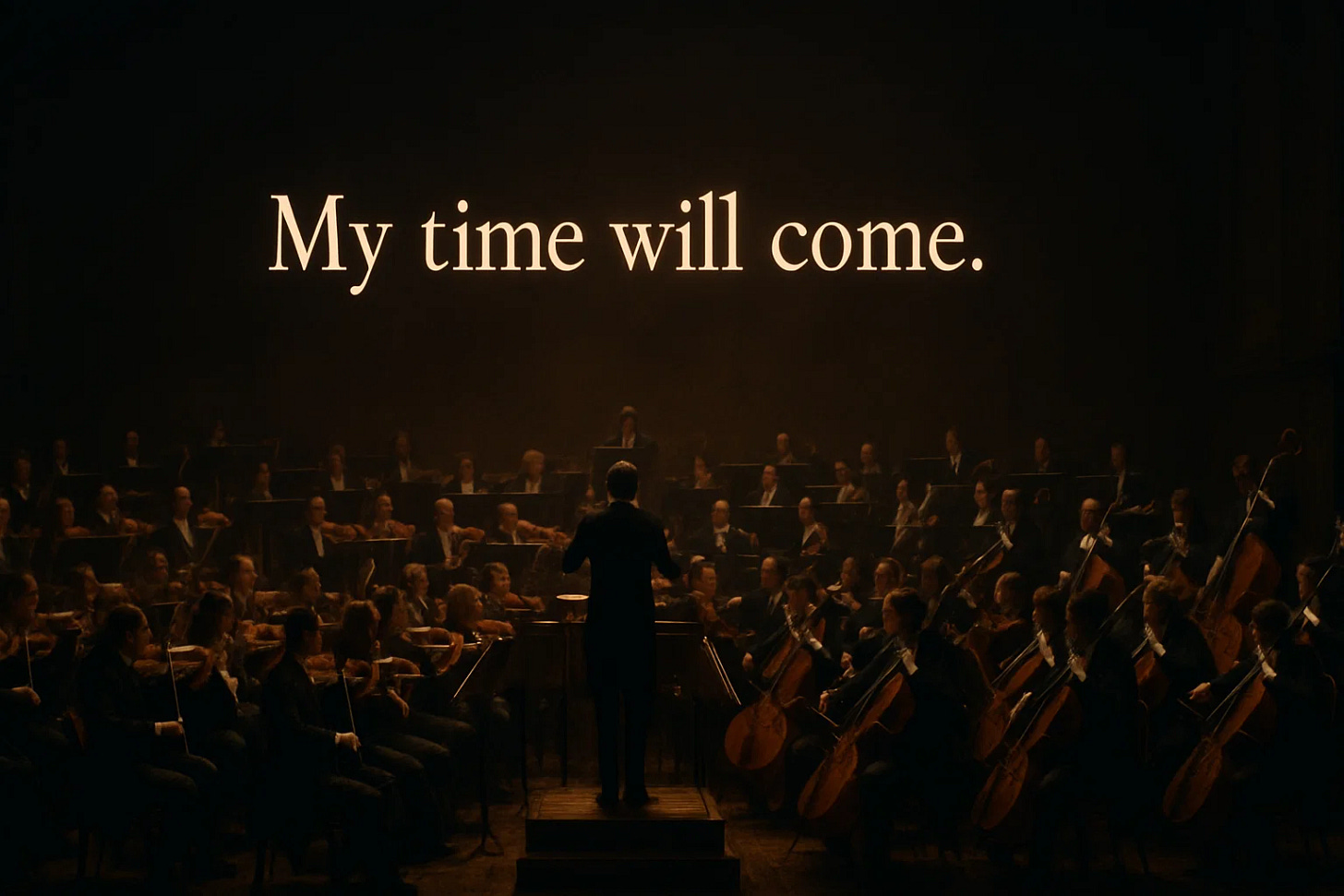

Mahler was mocked by critics and hounded by cultural gatekeepers. He was forced to convert from Judaism to Catholicism just to get a job in Vienna. His music was called excessive, neurotic, even “in bad taste.” He wasn’t embraced by the establishment—he fought it. He once said, “My time will come.” And he was right—but it didn’t come easily.

Bruckner, too, was ridiculed by academic critics like Eduard Hanslick, who dismissed his symphonies as bloated and formless. He was pushed into revising his work again and again by people who simply didn’t understand what he was trying to do. He wasn’t writing for professors. He was writing for God and the people.

So when you see these symphonies as “niche” or “specialist”—remember: they were never meant to be. I would even say it’s an injustice to the composers even to entertain the idea.

VIII. A Cultural Tragedy—and a Choice

In today’s world of short attention spans, we’ve lost something vital: the patience for slow, grand, meaningful art.

We flit from one dopamine hit to the next—headlines, clips, playlists, reels. Everything short. Everything is shallow. Everything now.

And in that noise, we’ve forgotten how to sit still. How to listen deeply. How to follow an arc of thought or emotion as it unfolds.

But the music is still here.

In your pocket. On your phone. Waiting.

You don’t need to go to Vienna. You don’t need to listen to all the Mozart symphonies.

Nothing stops you from putting on Mahler’s First, or Schubert’s Ninth, or Bruckner’s Seventh today.

The tragedy is not that this music is difficult. It’s that we’ve been conditioned to believe it’s not for us—that it’s some intellectual ritual, when in fact, it was always meant to elevate the human spirit.

And it still can.

But we are dangerously close to becoming a culture that forgets what it’s like to listen to something for an hour—without skipping.

To feel the tension build and break.

To be rewarded with something earned.

That’s what these symphonies offer. Whether we receive that gift or ignore it is up to us.

It’s a cultural tragedy—but also a personal choice.

One click. One quiet room. One act of attention.

That’s all it takes.

🎧 Recommended: Mahler’s Symphony No. 1 – Zubin Mehta with the Israeli Philharmonic

IX. The Composer’s Gift to Humanity

One way I like to think about music, especially these epic symphonies, is that they are the composers’ gift to humanity. They’re not puzzles. They’re not secret codes meant to be solved with a chart and a glossary. They are works of art meant to be cherished.

Great art doesn’t need to be explained. It only needs to be experienced. And if you open yourself up—if you simply allow the music in—you will be rewarded beyond measure.

All it takes is to close your eyes, put the phone away, and listen. That’s it. No effort, no analysis, no background in theory. Just listening.

What a gift that is:

The work is minimal. The reward is endless.

How foolish we are to refuse it.

X. Don’t Be Scared of Mahler

Let me say it plainly:

You don’t need to be a scholar.

You don’t need to read a programme note.

You don’t need to understand sonata form.

You just need to listen.

Mahler, Bruckner, Schubert—they didn’t write for specialists.

They wrote for people. For audiences. For you.

They wrote about life, death, grief, joy, and the long, strange journey from one to the other.

You owe it to your soul to experience the Adagietto from Mahler’s Fifth.

To sit in silence and let its tenderness wash over you like a whisper from another world.

And when that harp enters, so gentle, so unassuming—it teaches you something our world rarely does: how to be emotionally vulnerable without fear.

You owe it to your spirit to hear the finale of that same symphony explode into joy—

not cheap joy, but earned joy—an orgasmic, full-bodied release of life itself.

You owe yourself the long, slow unfolding of Schubert’s Ninth,

to sit with a piece that breathes like nature and walks beside you like time itself.

You owe your strength a symphony like Bruckner’s Seventh,

which doesn’t flatter you with emotion, but surrounds you with majesty.

And yes—there’s depth to this music. There’s theory. There’s form. There are libraries written about it. And when you’re ready, all of that will deepen your experience.

But you don’t need it at the start.

You don’t need to understand.

You need to feel it.

This music is not for the elite.

It is not for the past.

It is not a museum artefact.

It is the composer’s gift to humanity.

And you owe it to yourself to receive that gift.

To sit still. To listen. To be overwhelmed.

To walk through darkness and come out glowing.

To give your mind something vast.

To give your soul something noble.

To give your day one hour of real meaning.

I was intimidated once, too.

I thought I had to earn my way in.

But I didn’t.

And neither do you.

So don’t be scared of Mahler.

Be ready.

Be curious.

Be still.

And let him change your life.

If you enjoyed Philosophy: I Need It, and want to see more, you can support my work by buying me a coffee. Every contribution makes a real difference. Thank you!

Hmm, interesting. Thanks for recommending it here. It actually sounds very approachable to me. Will listen more.