Anders Zorn in Hamburg: Beauty Without Apology

How one exhibition remembered what a museum is for

I. The Blue Boy

Back in 2022, during a long journey across the United States, I found myself in Los Angeles. I’d heard of the Huntington, a mansion turned museum with one of the world’s finest collections of English art, and I couldn’t miss the chance to see The Blue Boy. Gainsborough’s masterpiece is one of the most beloved portraits ever painted. I looked forward to the moment of encountering him with reverence.

Instead, I was met with something close to desecration. Right in front of The Blue Boy’s rightful place hung a contemporary “reinterpretation”, a self-portrait by an “artist” I’ll refrain from naming, posed mockingly in imitation of the museum’s most prized possession. A parody hung before a masterpiece. And that, somehow, became the point. Instead of walking away uplifted, I left appalled, offended even, on Gainsborough’s and Mr Huntington’s behalf. How could such a thing hang in Mr Huntington’s house, right before his most prized possession?

From that moment, I became sceptical, almost cynical. Whenever I hear of a new exhibition, I expect irony, mockery, or some curatorial need to “update” the past. So when I heard that the Hamburger Kunsthalle was presenting a major Anders Zorn exhibition, I braced for disappointment.

And what a relief it was to be wrong.

II. The Red Man

The exhibition was enormous, with watercolours, etchings and oils side by side, each luminous. The watercolours didn’t even look like watercolours; they carried the depth and weight of oils, alive with colour and light. Zorn could paint a harbour, a crowd, a nude, or a royal portrait with equal conviction. His Midsummer Dance (1897) glowed with joy, peasants dancing in the Swedish twilight, a celebration of life’s pulse. Omnibus (1892) captured the bustle of Paris with astonishing immediacy, while his Self-Portrait in Red (1915), painted amid the First World War, shone with quiet defiance.

Each work carried the same spirit: a broad, unmistakable love of life.

He loved women; that’s obvious from his nudes. But it wasn’t lust or performance; it was admiration, an artist’s gratitude for beauty. He loved the good life, and he celebrated it. His nudes are not provocations but affirmations, sunlit bodies, glimmering water, the joy of being human. In a century that was turning toward despair, Zorn remained on the side of life.

And among all the paintings in the exhibition, there was one that genuinely stopped me, the portrait of Abby Marion Deering Howe from 1900. The image I took on my phone doesn’t come close to capturing its majestic force. In the room itself, the red is overwhelming in the best possible sense: not aggressive, not theatrical, but rich, full, saturated with life. The entire canvas glows.

She sits on a red couch, in a red dress, surrounded by that same atmosphere of red, and yet she doesn’t disappear into it. She emerges from it. Her presence commands the frame. The softness of the fabric, the subtle sheen on the silk, the warmth of the background, Zorn turns all of it into a celebration of her beauty, her sensuality, her dignity. It is sensual without being crude, elegant without being cold, vivid without being gaudy. It lives. It’s one of the most visually striking portraits I have recently seen, and you could feel people around the room pausing longer there, as if the painting were almost pulling them in.

This is the kind of work that shows exactly what I mean when I say Zorn loved life. There is no irony here, no mockery, no distancing device. He is not commenting on female beauty; he is affirming it. He paints her with admiration, with warmth, with that unmistakable Zorn confidence that life is good and therefore worth portraying in its fullness.

This painting alone could have carried the entire exhibition.

And then there is the portrait of Emma Zorn in the Paris Studio (1894), an extraordinary marital portrait. Many great artists, when painting their wives, slip into idealisation: the perfect setting, the perfect pose, a kind of sentimental beauty that says nothing true about the relationship. Zorn does the opposite.

He paints Emma exactly where she belonged in his life: in the studio, among his canvases, working with him. She stands in her red dress with white polka dots, sorting through his paintings, looking directly at him, at us, with a mixture of intelligence, calm assurance, and a familiarity that only comes from shared labour.

This isn’t a romantic fantasy. It’s a profound show of respect.

Emma wasn’t an accessory to his career; she was central to it. Their partnership was a remarkable artistic marriage: She managed his business affairs, curated his legacy, shaped his public image, and kept the entire enterprise functioning. She was the structure that allowed his genius to thrive.

And Zorn acknowledges that fact in the most honest way possible:

Not by pretending she was a decorative muse,

But by placing her at the centre of his creative world, holding his paintings, the extensions of his body, of his mind, of his vision, with complete natural authority.

In a sense, I see it as a kind of self-portrait.

Emma and the canvases together are Zorn.

She is holding him, his work, his identity, the two of them fused into the life they built.

It is, in its way, one of the most loving portraits imaginable, because it depicts not fantasy but truth: a marriage built on work, trust, and a shared life in art.

A portrait of a wife, yes, but even more, a portrait of a relationship.

If that portrait of Emma shows the inner world that shaped him, the village scenes show the outer world he never abandoned.

Both are Zorn, the intimate and the communal, the studio and the soil.

Two works stayed with me long after I left the room.

The first is Lucky with the Ladies (1883–1885), a watercolour so rich and full that I had to double-check the label; it simply doesn’t look like a watercolour. A group of villagers walking along a path, the young man escorting two women with a confidence that borders on playful pride. The colours, the fabric, the light, it is joyful, affectionate, gently sensual. Zorn treats these women with the same warmth and admiration he gives to aristocratic sitters. It is, again, that unmistakable positivity: a celebration of masculinity and femininity, of human presence, of the simple pleasure of being alive.

The second, Dance in the Gopsmor Cottage (1914), is even more revealing. A cramped room, bodies spinning, skirts flying, light flickering off the rafters. It has the energy of Degas, that same impressionistic immediacy, but instead of Parisian ballerinas, Zorn gives us villagers dancing in a rural cottage. It’s extraordinary: he borrows the language of high French Impressionism and plants it in the soil of his own people. It shows exactly who he was. No matter how many presidents he painted, no matter how many wealthy patrons sought him out, he always returned to these scenes, these people, this world.

This wasn’t nostalgia. It was loyalty. It was affection. It was identity.

And it shows something essential about Zorn: he was at ease among kings, but his heart never left the village.

Zorn was a man of the world. He travelled everywhere, Sweden, Paris, London, Venice, New York, and belonged to each without losing himself. He could paint American presidents and Swedish fishermen with the same dignity. From aristocratic portraits to peasant dances, he found the same nobility in work, movement, and light.

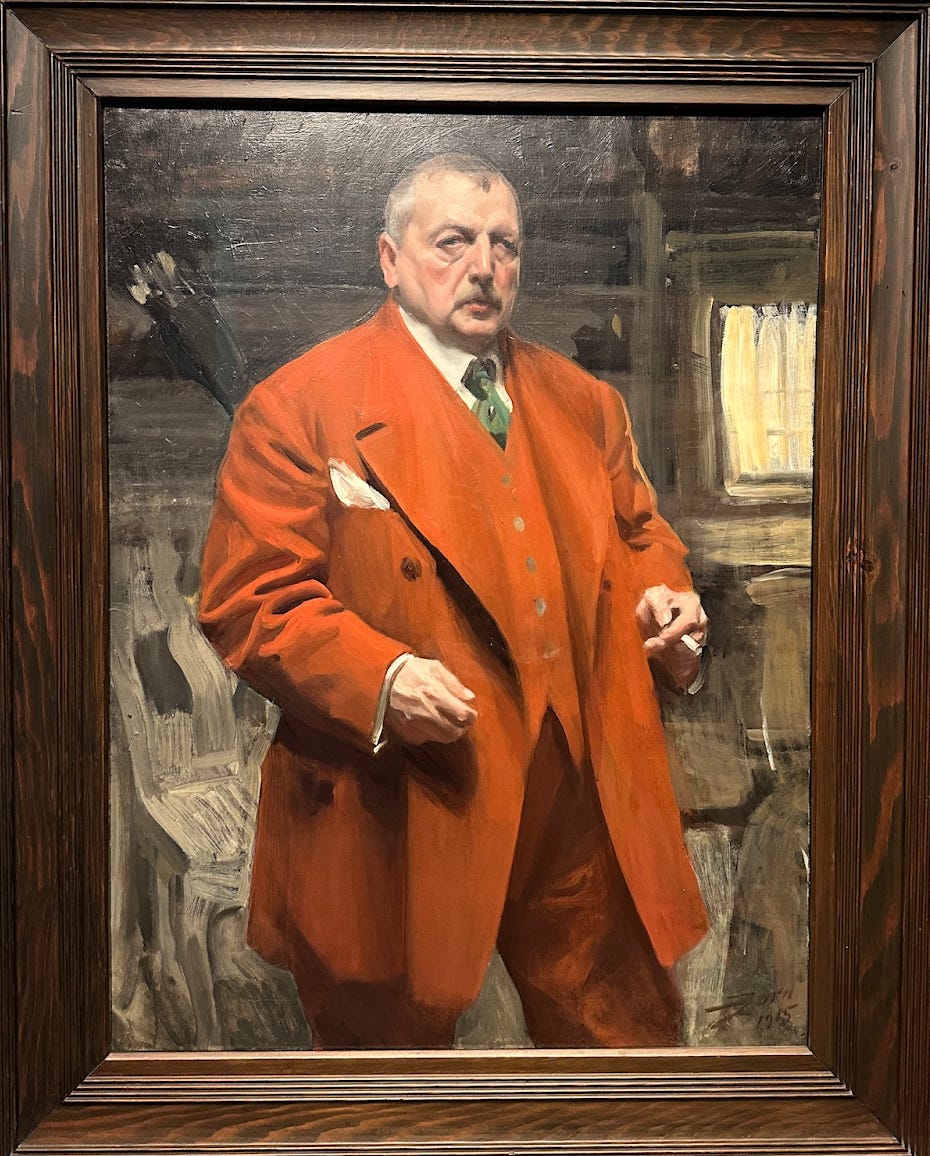

And then there is his self-portrait in the red three-piece suit, a painting that reveals more about Zorn the man than any biographical summary could. How often does one see a painter, especially in that era, dress himself in such bold colours? A red three-piece suit, a green tie, and yet nothing flamboyant or unserious about it.

It is confidence without pretentiousness.

Conviction without noise.

A proud sense of his own culture, his own taste, his own values.

You look at this portrait and understand that this was a man who refused to disappear into the background. He stands there holding his cigarette with a deliberate calm, a measured assurance. Nothing fast, nothing frantic, nothing hurried. This is the pose of someone who knows exactly who he is, where he comes from, and what he stands for.

It is extravagant, yes, but in the way beauty itself is extravagant: unapologetically. Zorn isn’t pretending to be exotic, nor is he retreating into dull simplicity. He is exactly himself: colourful, disciplined, rooted, and absolutely unafraid of being seen.

A self-portrait is always a declaration.

This one says: I am a man of the world, and I stand by myself without compromise.

He came from nothing and never forgot it. Born to humble beginnings in Mora, raised by his grandparents, he rose to paint kings and presidents. He was made rich by his own brilliance, not by birth or favour. Even success didn’t soften him; he remained loyal to his roots, establishing a prize and foundation to support other artists. He didn’t only create, he ensured others could.

Even the Great War didn’t break him. When Europe’s spirit collapsed, when many artists abandoned beauty for bitterness, Zorn kept painting the same lakes, the same light. It showed what he was made of: stern conviction, moral clarity, belief that art must affirm life, not lament it.

All of this, the life, the convictions, the loyalty to beauty, formed the man whose work I saw that day. And it mattered where I saw it. Zorn’s worldliness, his rooted confidence, didn’t hang in a vacuum; it hung in Hamburg, a city that has always lived between worlds.

III. The Right City

What place could be more fitting for such an exhibition than the Hamburger Kunsthalle, that junction between Scandinavia and the rest of the world. The Hanseatic city once embodied the very grandeur and abundance that Zorn’s art radiates: a worldly confidence, a love of craft, a celebration of life’s fullness. To see his work there felt symbolic, as if Hamburg itself recognised a kindred spirit, a man who turned worldly experience into beauty.

At the same time, only a few kilometres away, at the Elbphilharmonie, a “recomposed” Tchaikovsky Fourth Symphony was being performed, a mutilation presented as progress—two visions of art in one city: one affirming beauty, the other dismantling it. Hamburg contained within one day the entire struggle of our age, between those who create and those who only comment.

IV. The Moral Act of Curation

What struck me most was what the Kunsthalle didn’t do. They didn’t pair Zorn with some ironic counterpoint to prove their cleverness. They didn’t insert provocation or apology. Even the blurbs next to some of the paintings were to the point. They simply trusted the art. That restraint, today, is moral courage.

It’s sad that we’ve reached a point where such basic curatorial decency feels almost transcendent. To simply let beauty exist, without irony, without commentary, has become a moral act. In a more rational world, this would be taken for granted. But today, it feels like witnessing our once great civilisation waking up.

One might think: so what, they just put up an exhibition and refrained from adding commentary to make it “relevant.” They didn’t plaster it with explanations or attach their narcissism to the painter’s greatness. They simply let him speak. Yes, that’s their job.

But we live in an age of narcissism and nihilism, where curators, those meant to be guardians of the greatest achievements of humanity, have not only failed in their duty but often work to dismantle the very thing they were entrusted to protect. That’s why this matters. Today, simply doing the right thing has become exceptional.

The Kunsthalle is not perfect; it carries its share of modern tendencies. But in this instance, it acted with integrity. And I commend that.

It’s outrageous when you think about it. Try explaining to a 19th-century Viennese or Parisian that people now go to museums expecting mockery, that curators, once guardians of beauty, now use masterpieces as props for their own destruction. He would think you’d gone mad. For him, a museum was a temple. Reverence was assumed. The very idea that one would hang a parody before The Blue Boy or “recompose” Tchaikovsky would have sounded like a nightmare. And yet that is our normal.

That is why this exhibition in Hamburg was more than an aesthetic experience. It was a moral act that maintains civilisation in an age of decay. It is easy to underestimate the importance of something so seemingly ordinary, a museum doing its job, but in times like ours, it becomes an act of courage.

It was, simply, an incredibly positive and inspiring exhibition, radiant, humane, and utterly free of cynicism. No irony, no nihilism, no apology for beauty. Just art that believes in life.

I’m so glad I happened to be in Hamburg at that time. To stand before those paintings was to remember what art can be: generous, alive, human. If you’re anywhere near Hamburg, go. There’s still time. See it for yourself. It’s a reminder that beauty still exists, and that sometimes, even now, a museum can get it exactly right.

If you enjoyed Philosophy: I Need It, and want to see more, you can support my work by buying me a coffee. Every contribution makes a real difference. Thank you!

Totally agree about the awfulness of contemporary curation and direction. It has killed theatre stone dead and all the arts are suffering. "Re-imagined", "As you have never seen it before" and so on. I am thankful that I did see so much before this nasty, egotistical trend came in.

What a perfect and deserved paean of praise to Anders Zorn, thank you. We discovered him only a couple of years ago on holiday in Mora. Why is he not better known? Technically in particular as you say "The watercolours didn’t even look like watercolours; they carried the depth and weight of oils, alive with colour and light." but also for the sheer zest and vitality he conveys. Maybe loving life is out of fashion.