After the Sirens: Over Eternal Rest

A Meditation on Art, War, and Endurance

(Written just after the war with Iran)

I. Adagio: The Draft That Waited

(Langsam. Mit schwerem Ausdruck)

I wasn’t planning to write about painting. Not today.

Lately, it’s been only war.

Israel. Surrender.

America’s pressure. Iran’s missiles.

I’ve been writing essays like dispatches—fast, clear, and relentless.

And they’ve struck a chord. The response has been unlike anything I’ve ever known.

It’s as if the world were waiting for someone to say it plainly. So I did.

But today, without thinking, I opened my Substack drafts.

And there it was.

No title. No paragraph. Just a single image:

Isaac Levitan’s Over Eternal Rest.

A painting I must’ve placed there over a year ago. A fragment. A whisper I hadn’t yet answered.

I hadn’t written a word beneath it.

It just sat there. Waiting.

And now I know why.

Because now, after the ruins of these past weeks—after the missiles and the sirens,

after my grandmother’s house was damaged by an Iranian strike,

after the shelters,

the stress,

the unbearable sights of missile hits in my Tel Aviv—

now I understand what this image meant.

What it still means.

That small church. Alone on the bluff.

An adagio in wood and wind. Silent, unmoving, unresolved.

The river vast. The trees are barely standing.

The sky—thick, heavy, almost unbearable.

But the chapel remains.

Not defiant in the vulgar sense.

But upright.

Still.

Stillness—not as absence,

but as the discipline of breath held.

A quiet declaration.

This, I now understand, is what I admire.

II. Scherzo: You Are An Addict

(Schnell und kräftig)

You are an addict.

An addict to that which you cannot change.

Obsessed with that which is above you,

beyond your control.

What can you do?

Can you stop a missile in midair?

Can you change the course of history?

No.

And the more you try,

the worse you’ll feel.

The lower you’ll sink.

You are a coward!

You hurl your soul at missiles that laugh at your rage.

You use the world’s collapse

to ignore your own.

Why aren’t you obsessed

with what is yours to command?

Halt the bickering.

Stop the spiralling.

Focus.

If there is one thing you still control,

it is how you act.

So act.

Upright.

And face the waters, head on.

III. Intermezzo: Between Nussbaum and Levitan

(Ruhig, aber nicht schleppend)

My last painting essay was published almost two months ago.

It was about Felix Nussbaum.

A hunted man.

A man who painted sunflowers before he painted skeletons.

A man who wanted nothing more than to be ordinary, just to paint, just to live—

and was instead turned into a prophet of doom.

That essay ended not with The Triumph of Death,

but with the sunflowers he never got to paint.

Because I refused to let the final image be death.

I refused to let his murder be his definition.

And yet since then—

since that train ride to Osnabrück,

since walking through that museum’s metal corridors,

since slipping out the back exit of that museum into the green, postcard-pretty German streets—I haven’t returned to painting at all.

Not until now.

Because the moment I returned to Tel Aviv, everything turned to drama.

The sirens began.

Sleepless nights.

That horrible beeping sound.

The bomb shelter.

I couldn’t breathe.

I wrote The Song of War from inside one of them—six movements, from inside the shelter.

A dissonant interval. Sirens, shelter, smoke. A whole movement without resolution.

The only thing I could write was verse.

No prose. No art essays. No sunflowers.

Only fear, irony, Mahler, and grief.

Now, I come back to painting.

Not to Nussbaum’s palette of brown and bone—

but to Levitan’s palette of silence and stillness.

Not to the hunted, but to the exiled.

Not to the man painting death inside Europe—

but the man painting life from the margins of it.

Nussbaum paints the end of civilisation from within it.

Levitan paints the essence of civilisation while excluded from it.

Both were Jews.

Both were artists.

Both were men of vision in a continent that could not tolerate them.

And both, in their own way, refused to vanish.

You could say that I stand between them.

One foot in Europe.

One foot in Tel Aviv.

Carrying the memory of one,

and the longing of the other.

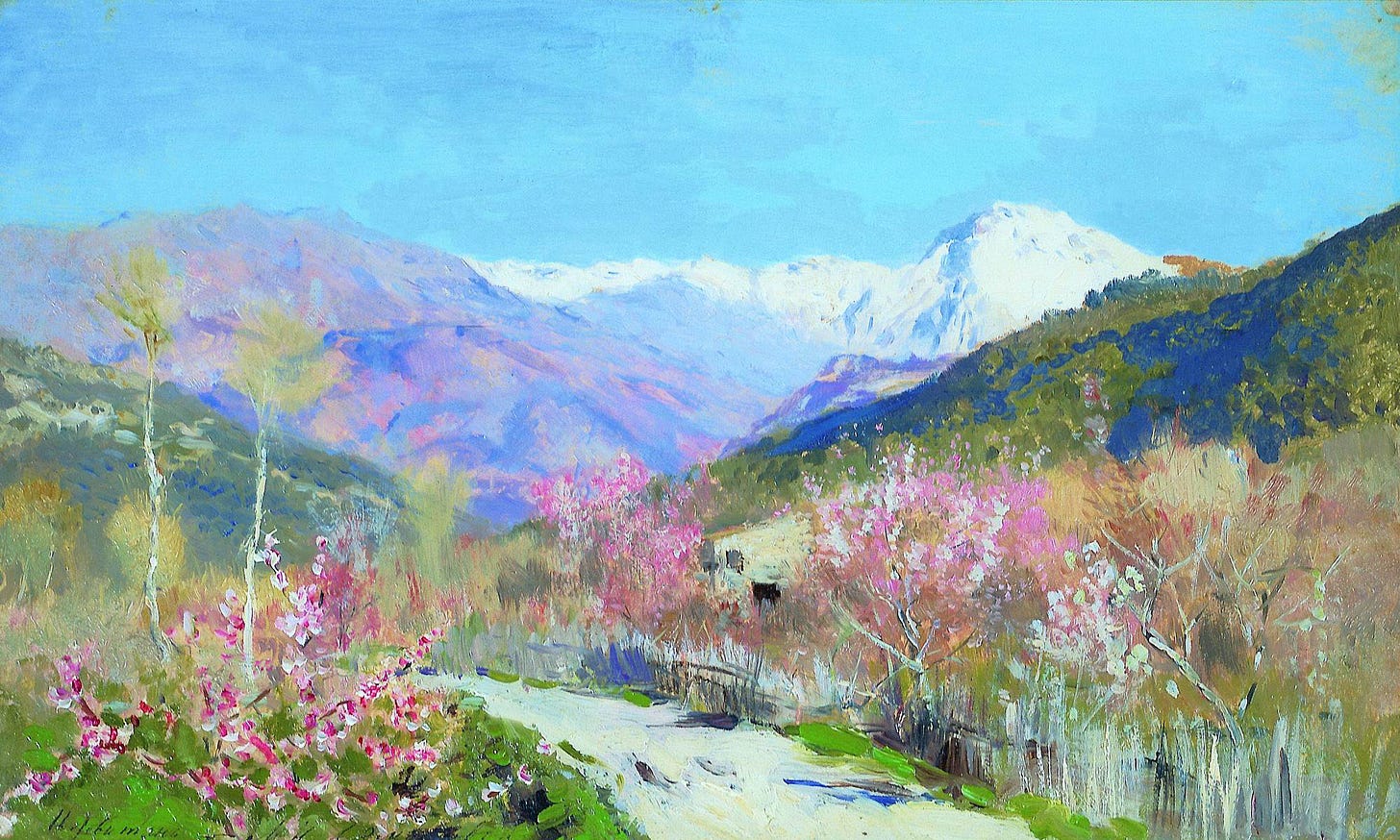

IV. Andante: Spring in Italy

(Bewegt, doch zart)

Beyond the turbulence of Central and Eastern Europe—

beyond Germany, beyond Russia,

beyond the shadowed lands of the north—

there is Spring in Italy.

And what a sight that is.

Snow-capped mountains rise in the distance.

Closer in, pink-blushed valleys roll into soft hills.

A quiet village nestles below.

A winding path threads the hills.

Oleander spills over the tall grass,

Delicate cypress trees sway.

You can hear the wind whirl distant cowbells.

Perhaps even catch, in the air,

the faint smell of limoncello—not the drink,

but the sense of life.

Let us breathe in the spring.

Let us breathe in the sunlight.

For we must remember—

that place exists, too.

There can be a dolce vita.

And in Italy’s spring,

I hear the chapel’s stillness again—

a whisper that Tel Aviv, too, might breathe.

V. Finale: And Yet, I Write

(Mit Hoffnung, doch zitternd)

Perhaps that’s the quiet triumph.

That between the hunted painter and the silenced one,

between Nussbaum’s scream and Levitan’s hush,

between the chaos of war and the illusion of peace,

between the sirens and the lull—

I remain.

Not intact.

Not innocent.

But standing.

Like that chapel, I remain.

Not defiant in posture,

but stubborn in presence.

Still.

And stillness—true stillness—is not the silence of the grave,

but the breath you hold before you speak again.

It is the pause before a new act.

And so, from Osnabrück to Tel Aviv,

from Levitan’s Italy to this shuttered room,

I remember:

There is painting.

There is writing.

There is breath.

There is music.

There is beauty.

And that means—

I still live.

Am Israel Chai!

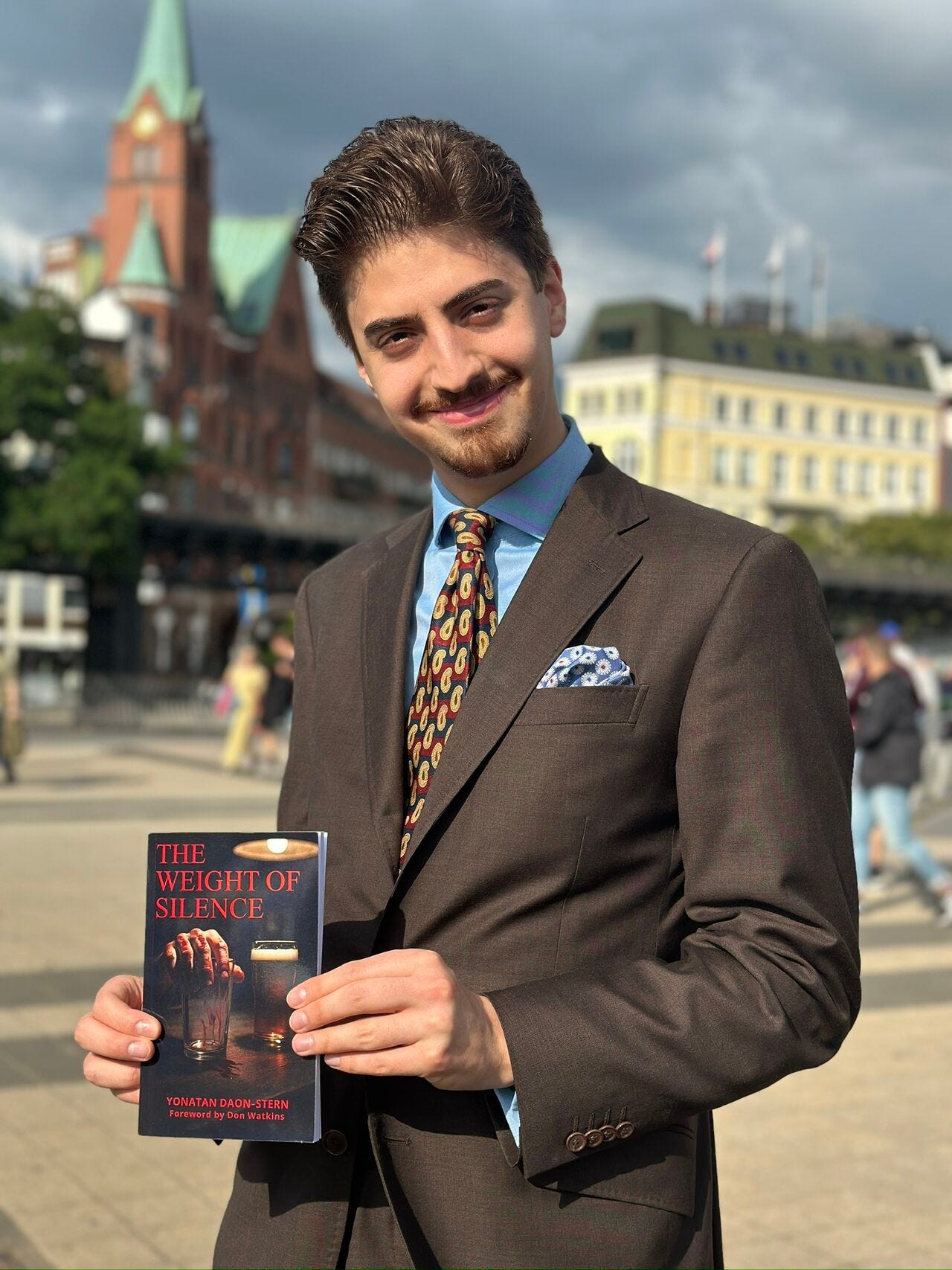

Enjoyed this piece?

I’ve just released my debut novella, The Weight of Silence. You can buy it on Amazon.

If you want to support my broader work—fiction, essays, and everything in between—consider becoming a monthly member, or make a one-time contribution here. Every bit helps me create more and better.

What a lovely essay. I saved it off.

That final painting of Levitan's, the one with the church, the one he finished shortly before he died but which he started long before, the one he struggled with, tweaking it and tweaking it until he got it right, not looking like the landscape in real life but looking like the landscape he needed, I was thinking what a statement it is.

Because Levitan's own life was a dance between the raindrops. A penniless orphan, he only got two years of art school. Immensely talented, he found a mentor who championed him and he studied with a scholarship, until that mentor died and the little Jew was thrown out of school. To his regret, he never got really good with the figure. He turned his disadvantage into an advantage and became the best landscape painter ever, but still.

Think how when he was living, Jews were being decimated by pogroms, expelled from their homes. They were in no position to help him. What help he received was from non-Jews. He painted at their dachas, they put him up. Purely from merit he attracted the great collector Tretyakov as a patron, so he showed alongside the best painters of the day. It was only through the help of non-Jewish friends that he avoided being sent to Siberia. Expulsion was always hanging over his head. I think of his Vladimirka Road (https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/44/Vladimirka_%28Levitan%29.jpg/640px-Vladimirka_%28Levitan%29.jpg), the road to Siberia, as bleak as bleak gets.

It's like he spent his whole life with a go-bag, depending on the kindness of friends and strangers who forgave him for being a Jew because of his excellence at painting.

He had a heart condition and had been sick for years when he painted "Over Eternal Rest." He could have painted something with the dread of "The Vladimirka Road" as he was struggling in vain to heal, but he didn't. "Over Eternal Rest" is a profoundly optimistic piece. Never mind that he paints a church and not a synagogue — he was painting for a Christian audience, after all, and painting in their visual language. The grandeur, the conceptual abstraction, and the optimism make "Over Eternal Rest" a profoundly Jewish piece. He had a lot of reasons for despair, but he refused despair.

He's one of my heroes.